Thomas Wriothesley 1608-1661

Wriothesley, Thomas, fourth earl of Southampton (1607/8–1667), politician, was born at Little Shelford in Cambridgeshire on 10 March 1608, the second but only surviving son of Henry Wriothesley, third earl of Southampton (1573–1624), and Elizabeth Vernon (b. 1571, d. Dec 22, 1655). He was educated at Eton College (1613–19) and St John's College, Cambridge (1625–6). Southampton spent most of the later 1620s and early 1630s in France and the Low Countries. On 18 August 1634 he married his first wife, Rachel de Beaujeu (1603–1640), eldest daughter of Daniel de Massüe, seigneur de Ruvigny, and widow of Elysée de Beaujeu, at Charenton in France. They moved to England shortly afterwards and, before Rachel's death in childbirth on 16 February 1640, they had two sons (Charles and Henry, who died young), and three daughters (Magdalen, who died an infant, Elizabeth, and Rachel.

Visitors may consult content provided below by Oxford Publishing Limited for research and study purposes only. Any further use, including, but not limited to, unauthorized downloading or distribution of images or editorial content is strictly prohibited. Visitors must contact the Oxford Publishing Limited (facilitated by PLSclear) at plsclear@pls.org.uk .

ODNB ENTRY Wriothesley, Thomas, Fourth Earl of Southampton (1608-1667) By David L. Smith

Wriothesley, Thomas, Fourth Earl of Southampton (1608–1667), politician, was born at Little Shelford in Cambridgeshire on 10 March 1608, the second but only surviving son of Henry Wriothesley, third earl of Southampton (1573–1624), and Elizabeth Vernon (b. 1573, d. in or after 1655). He was educated at Eton College (1613–19) and St John's College, Cambridge (1625–6). Southampton spent most of the later 1620s and early 1630s in France and the Low Countries. On 18 August 1634 he married his first wife, Rachel de Beaujeu (1603–1640), eldest daughter of Daniel de Massüe, seigneur de Ruvigny, and widow of Elysée de Beaujeu, at Charenton in France. They moved to England shortly afterwards and, before Rachel's death in childbirth on 16 February 1640, they had two sons (Charles and Henry, who died young), and three daughters (Magdalen, who died an infant, Elizabeth, and Rachel [see Russell, Rachel, Lady Russell]).

Relations with Charles I

Following his return to England, Southampton found himself in debt after an unwise bet at Newmarket and began selling timber on his main estates at Titchfield in Hampshire. Charles I took advantage of this to buy 1000 of Southampton's best oak trees for shipbuilding at a reduced price of £2294 10s. Southampton then became one of the most notable victims of Charles's attempts to revive ancient claims to royal forest. In October 1635 a forest court chaired by the earl of Holland at Winchester challenged Southampton's title to the greater part of his estate at Beaulieu in the New Forest. Charles claimed that the lands were royal forest, which would have had the effect of reducing the rents paid to Southampton from £2500 to £500 per annum. By exploiting this legal technicality Charles forced him to beg for the restitution of lands that were rightfully his, but Southampton petitioned for relief and Charles relented in July 1636.

Southampton's bitterness against the king may well help to explain why he insisted in the Short Parliament that discussion of grievances should precede supply. Hyde later wrote that by 1640 Southampton ‘had never had any conversation in the Court, nor obligation to it; on the contrary he had undergone some hardness from it’. He had ‘a particular prejudice’ against Strafford, but became alarmed ‘as he saw the ways of reverence and duty towards the King declined’ (Clarendon, Hist. rebellion, 2.530). These attitudes were closely associated with ‘a perfect detestation of all the Presbyterian principles’. Southampton was ‘a man of great and exemplary virtue and piety’ who ‘strictly observed the devotions prescribed by the Church of England’ and was ‘averse and irreconcileable to the sedition and rebellion of the Scots’ (Life of … Clarendon, 3.238).

It seems that this attachment to the crown and the church ultimately overcame Southampton's bitterness at the way that Charles I had treated him: on 3 May 1641 he was one of only two peers (the other was Lord Robartes) who refused to assent to John Pym's protestation following the revelation of the first army plot; Southampton voted against Strafford's attainder, and on 3 June was appointed lord lieutenant of Hampshire; at the beginning of November, Charles asked Nicholas ‘to thanke Southampton in my name, for stopping the Bill against the Bishops’ (Diary of John Evelyn, 4.114); and by the middle of that month Henrietta Maria regarded Southampton's proxy as vitally important in the mobilization of the king's supporters within the upper house. Southampton was sworn a gentleman of the bedchamber on 30 December, and was appointed a privy councillor on 3 January 1642. He was given leave by both the king and the Lords to leave Westminster in February, but initially chose to remain there, on 5 March entering his protest against the militia ordinance. He obtained leave to go to York on 17 March and had arrived there by the twenty-seventh. It is possible that he was back in London about 24 April when he married his second wife, Elizabeth Leigh (1620?–1658), eldest daughter of Francis Leigh, Lord Dunsmore (created earl of Chichester in 1644), and his second wife, Audrey Boteler. They had four daughters, only one of whom, Elizabeth, survived youth.

Promoting peace

Although Southampton was among those who in June 1642 engaged to provide the king with forces, throughout the civil wars he remained deeply committed to seeking an accommodation with the houses. Immediately after the king raised his standard Southampton advised him that a message to parliament ‘might do good, and could do no harm’ (Clarendon, Hist. rebellion, 2.300). Charles eventually agreed to send Southampton—together with Edward Sackville, earl of Dorset, Sir John Colepeper, and Sir William Uvedale—to inform the houses of his ‘constant and earnest care to preserve the public peace’ (ibid., 2.304). However, when he entered the Lords, Southampton was ordered to withdraw from the house, to pass the message to the gentleman usher, and then to leave London immediately.

Southampton nevertheless persisted in promoting peace talks. He was one of the king's commissioners at the treaty of Oxford (February–April 1643). Then, in December 1644, he and the duke of Richmond acted as the king's messengers to the houses, requesting the appointment of commissioners which led to the treaty of Uxbridge (January–February 1645), although the talks again proved abortive. Later that year, when the prince of Wales was sent to the west country with his own council, Southampton expressed a particular wish to remain with the king and continued to urge him to bring the war to an end. In April 1646 he was involved in a further attempt to reach agreement with the parliamentarian army at Woodstock, and on 20 June he was one of the privy councillors who signed the Oxford articles of capitulation; the city formally surrendered four days later.

Before Southampton left Oxford he received a rebuke from Prince Rupert which led to a quarrel in which the prince sent him a challenge. However, friends of both parties intervened and the threatened duel never took place. In October 1647, Southampton was one of a small circle of royalist peers whom the king summoned to Hampton Court to advise him. The following month, during his flight from Hampton Court, the king visited Southampton at Titchfield, and the earl briefly followed him to the Isle of Wight. Towards the end of March 1648, Viscount Saye and Sele and several Commons allies—including Sir John Evelyn, William Pierrepont, and possibly Oliver Cromwell—attempted a personal approach to Charles I. They tried to enlist Southampton's help, but he refused to become implicated in such a contravention of the vote of no addresses. In the end he informed them bluntly:

my lords, I must tell you that I shall as a sworne privy councillor to his Ma[jes]tie give him such advise as is best and safest for him, but my lords you shall not heare nor be privy to what I say. (Bodl. Oxf., MS Clarendon 31, fol. 54v)

Southampton was among the peers permitted to attend the king on the Isle of Wight during the treaty of Newport, and he was also one of those who were with Charles during his trial. Following the king's execution, he obtained leave to stay in the palace of Whitehall, where it is said that he witnessed Cromwell approach Charles's corpse, consider ‘it attentively for some time’, and then mutter the words ‘cruel necessity’ (J. Spence, Observations, Anecdotes, and Characters of Books and Men, ed. J. M. Osborn, 1, 1966, 244). Finally, Southampton attended the king's funeral at Windsor on 8 February.

Parliament's treatment of Southampton's estates was relatively lenient. In November 1645 the committee for the advance of money had assessed him at £6000, although there is no evidence that this sum was ever paid. In the autumn of 1646 he begged to compound under the Oxford articles and was assessed at the rate of one-tenth, or the value of two years' income from his estates, and on 26 November his fine was set at £6466. In the autumn of 1648 the Commons confirmed his composition fine and ordered him to be pardoned for his delinquency and the sequestration to be taken off his estates. There is, however, no evidence that this fine was ever paid, and thereafter the committee for compounding apparently ceased to pursue him.

After Charles I's execution

After the king's execution Southampton lived in retirement in Hampshire. Although the council of state kept an eye on him, his political activities were extremely limited throughout the 1650s. He was deeply loyal to Charles II and in October 1651, during the king's flight after the battle of Worcester, he sent word from Titchfield that he had a ship ready for Charles. The king had already secured a boat to take him to France but he ‘ever acknowledged the obligation with great kindness, he being the only person of that condition who had the courage to solicit such a danger’ (Clarendon, Hist. rebellion, 5.211). After the king's escape Southampton ‘had still a confidence of His Majesty's restoration’ (Life of … Clarendon, 3.237). Yet Clarendon thought the earl ‘of a nature very much inclined to melancholic’ (Clarendon, Hist. rebellion, 2.529) and Southampton apparently believed that there was little chance of overthrowing the republic in the immediate future. His advice to Charles was always ‘to sit still, and expect a reasonable revolution, without making any unadvised attempt’, and he ‘industriously declined any conversation or commerce with any who were known to correspond with the King’ (Life of … Clarendon, 1.338–9).

Southampton declined to recognize the republican regime, and was not among those royalists known to have taken the engagement. According to Clarendon, Cromwell ‘courted’ the earl, but Southampton:

could never be persuaded so much as to see him; and when Cromwell was in the New Forest, and resolved one day to visit him, he being informed of it or suspecting it, removed to another house he had at such a distance as exempted him from that visitation. (Life of … Clarendon, 1.338)

There were occasional exceptions to Southampton's general quietism, most notably in November 1655 when he refused to give Major-General Kelsey particulars of his estate to permit assessment for the decimation tax, and as a consequence was briefly imprisoned in the Tower. He claimed that the decimation tax violated the Oxford articles, under which he had surrendered and compounded for his estates, and also the Rump Parliament's Act of General Pardon and Oblivion (February 1652). As under Charles I, he strongly defended legal propriety and challenged any policies that he perceived as breaches of the rule of law.

Southampton was released from the Tower by the end of 1655, and from then until the Restoration he lived very quietly, avoiding any involvement in royalist conspiracies. Southampton's second wife died late in 1658, and the following year, on 7 May, he married his third wife, Frances, née Seymour (c.1620–1680/81), widow of Richard Molyneux, second Viscount Molyneux of Maryborough (d. 1654), and daughter of the marquess of Hertford. He remained on very friendly terms with Hyde, and corresponded regularly with him throughout the interregnum. In June 1659 Hyde assured John, Viscount Mordaunt, that he would find Southampton ‘one of the most excellent persons living. Of great affection to the King; of great honor; and of an understanding superior to most men’ (Abergavenny MSS, 204). Hyde greatly valued Southampton's advice and regularly asked for his opinions; their close friendship, together with the king's favour, explains Southampton's appointment to high office at the Restoration.

Service to Charles II

On his arrival at Canterbury on 27 May 1660 Charles II appointed Southampton to the privy council and created him a knight of the Garter. On 8 September he was appointed lord treasurer, an office which he held until his death. Throughout these years Southampton was keen to strike a balance between avoiding a vindictive settlement while at the same time ensuring that the restored monarchy was financially secure and not dependent upon parliament. Ludlow praised his magnanimity for insisting in August 1661 that those exempted from the general pardon be given fourteen days to save themselves. Six months later Southampton opposed the excessive use of force to suppress Venner's rising in terms which were wholly consistent with the attitudes he had evinced earlier in his career:

They had [he said] felt the effects of a military government, though sober and religious, in Cromwell's army: he believed vicious and dissolute troops would be much worse: the King would grow fond of them, and they would quickly become insolent and ungovernable: and then such men as he was must be only instruments to serve their ends. (Burnet's History, 1.280)

He begged Clarendon to avoid anything that smacked of arbitrary rule and to preserve lawful, constitutional government; Clarendon, whose own commitment to the rule of law was deep, was won over by these arguments. Southampton consistently opposed the creation of a standing army, partly on grounds of cost, but also because he disliked any hint of authoritarian government.

A similar magnanimity characterized Southampton's attitudes towards the church. Burnet praised his commitment to ‘moderating matters both with relation to the government of the Church and the worship and ceremonies’ (Burnet's History, 1.316). Southampton sought to make the church as comprehensive as possible, and hoped that at least the more moderate presbyterians could be encompassed within it. He was one of the peers who tried to soften the terms of the Act of Uniformity, although their efforts were only partially successful. There is some evidence that his stance did not endear him to some members of the Restoration episcopate. Equally, he wanted such comprehension to be established by statutory means and, like Clarendon, he strongly resisted the king's attempts in 1662–3 to introduce a bill that would have enabled him to issue dispensations from the Act of Uniformity. Both Southampton and Clarendon ‘were very warm against it, and used many arguments to dissuade the King from prosecuting it’ (Life of … Clarendon, 2.344); both actively opposed the bill when it came before the Lords and helped to ensure that it was dropped. According to Clarendon, Southampton even expressed the view that the Indulgence Bill was ‘unfit to be received … being a design against the Protestant religion, and in favour of the papists’ (ibid., 2.345). Southampton regarded such use of royal prerogative powers as unacceptable, and clearly remained profoundly attached to a vision of royal powers tempered by the rule of law. Indeed, Burnet later claimed that Southampton blamed ‘all the errors’ of Charles II's reign on his ‘coming in without conditions’ (Burnet's History, 1.162), and even criticized his friend Clarendon for giving so favourable an impression of the king in 1660 that such conditions were not deemed necessary.

The hallmarks of Southampton's conduct as lord treasurer were caution, conscientiousness, and incorruptibility. Burnet wrote that ‘he was an incorrupt man, and during seven years management of the Treasury he made but an ordinary fortune out of it’ (Burnet's History, 1.171). Southampton refused to derive personal benefit from the office, and reached an agreement with the king whereby he received a fixed annual salary of £8000. He lamented that his own example of restraint was not followed by the king and many of his other courtiers: he made a number of urgent representations to Charles, especially in 1663–5, warning him that ‘the revenue is the centre of all your business’ (BL, Harleian MS 1223, fol. 202), but his calls for a policy of retrenchment were of only limited effect. According to Clarendon, in 1662 Southampton suggested the sale of Dunkirk as a way of boosting income, and in 1665 he strongly resisted the approaching war against the Dutch republic, conscious that this would only disrupt trade, diminish customs revenues, and drain the exchequer.

Disillusionment and final years

By the mid-1660s Southampton's disillusionment with the spendthrift king, together with deteriorating health, led him to withdraw more and more from active public work. In 1664 Lord Arlington, Baron Ashley, and Sir William Coventry asked the king to remove Southampton, complaining that he was delegating all his work to his secretary, Sir Philip Warwick. Although Clarendon successfully headed off this appeal, during the autumn of 1665 there was a further proposal, this time backed by James, duke of York, to replace Southampton with a commission. From then until his death rumours of the lord treasurer's replacement continued to circulate regularly.

These attacks took place against a background of worsening illness, and towards the end of 1666 Southampton fell gravely ill. After his death a large stone was discovered in his bladder, and one kidney was also found to be much enlarged. Southampton had never been robust—Sir Edward Walker wrote of his ‘infirm body’ (Bodl. Oxf., MS Ashmole 1110, fol. 170)—and after bearing the very painful illness with great bravery he died at his London home, Southampton House, on 16 May 1667 and was buried at Titchfield on 18 June. Clarendon mourned his friend and colleague, and summed him up as ‘a person of extraordinary parts, of faculties very discerning and a judgment very profound’; and ‘a man of great and exemplary virtue and piety’ (Life of … Clarendon, 3.229, 238).

DAVID L. SMITH

-

Clarendon, Hist. rebellion · The life of Edward, earl of Clarendon … written by himself, new edn, 3 vols. (1827) · Bodl. Oxf., Clarendon MSS · TNA: PRO, state papers domestic, Charles I, SP 16 · TNA: PRO, state papers domestic, interregnum, SP 18 · TNA: PRO, committee for sequestrations MSS, SP 20 · TNA: PRO, committee for compounding MSS, SP 23 · JHL, 3–11 (1620–66) · Diary of John Evelyn, ed. W. Bray, new edn, ed. H. B. Wheatley, 4 vols. (1906) · GEC, Peerage, new edn · The Nicholas papers, ed. G. F. Warner, 1, CS, new ser., 40 (1886) · The Nicholas papers, ed. G. F. Warner, 2, CS, new ser., 50 (1892) · The Nicholas papers, ed. G. F. Warner, 3, CS, new ser., 57 (1897) · The Nicholas papers, ed. G. F. Warner, 4, CS, 3rd ser., 31 (1920) · D. L. Smith, Constitutional royalism and the search for settlement, c. 1640–1649 (1994) · BL, Sloane MS 1116 · BL, Add. MS 12514 · Burnet’s History of my own time, ed. O. Airy, new edn, 2 vols. (1897–1900); suppl. , ed. H. C. Foxcroft (1902) · The manuscripts of the marquess of Abergavenny, Lord Braye, G. F. Luttrell, HMC, 15 (1887)

-

Hants. RO, personal, official, family, and estate papers"|" Leics. RO, corresp. with earl of Winchilsea

-

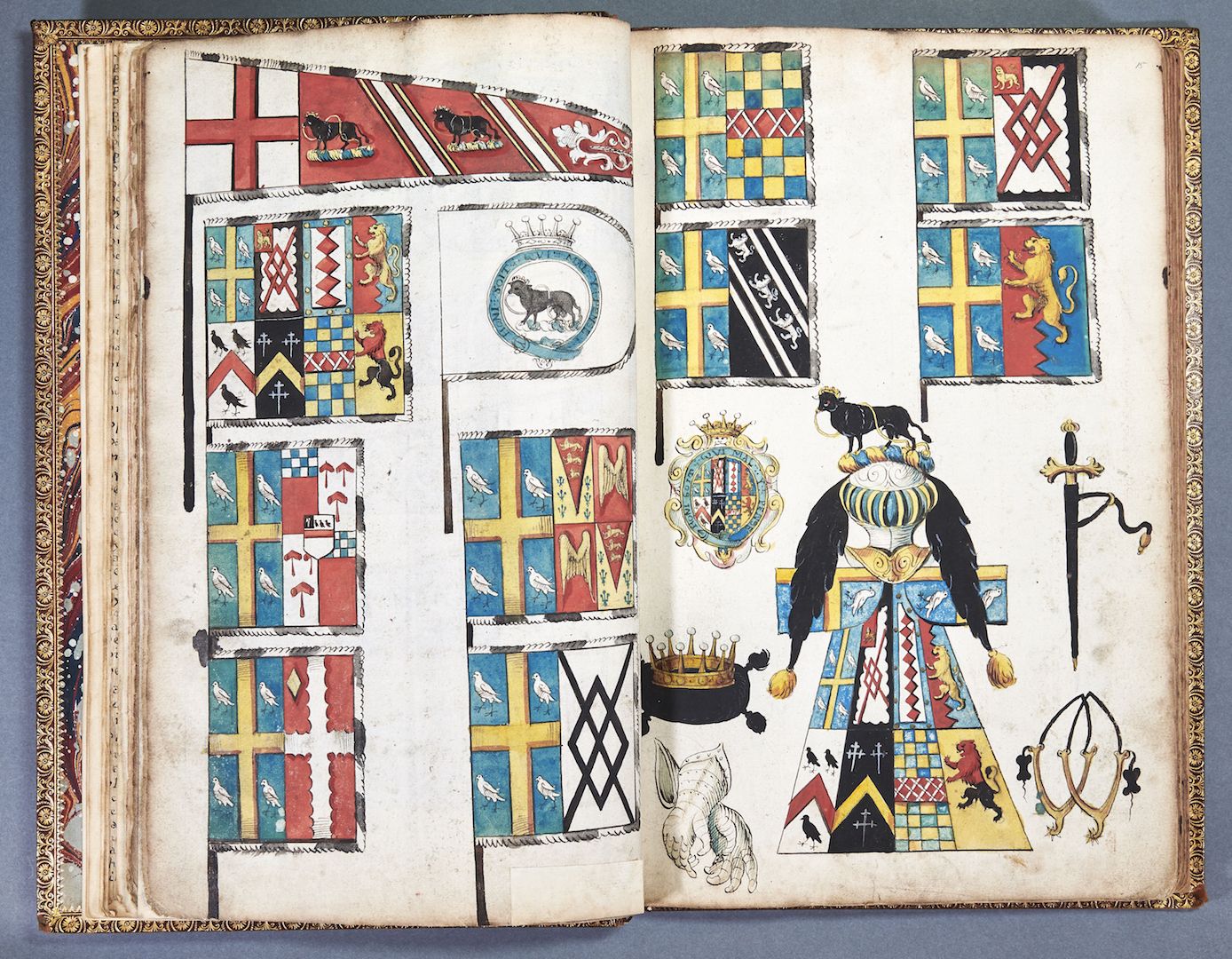

S. Cooper, miniature, 1661, Woburn Abbey, Bedfordshire · P. Lely, portrait, c.1661; Christies, 8 July 1998, lot 29 [see illus.] · T. Simon, silver medal bust, 1664, NPG; repro. in E. Hawkins, Medallic illustrations of the history of Great Britain and Ireland, 2 vols. (1885), pl. XXI · P. Lely, portrait, Woburn Abbey, Bedfordshire · oils (after P. Lely, c.1661), NPG · portrait, Welbeck Abbey, Nottinghamshire

-

£3233 p.a. in 1646: TNA: PRO, committee for compounding MSS, SP 23/3, 307

ODNB ENTRY 1900

Wriothesley, Thomas, Fourth Earl of Southampton (1608-1667) by Sidney Lee

Wriothesley, Thomas, Fourth Earl of Southampton (1607–1667), second but eldest surviving son of Henry Wriothesley, third earl of Southampton [q.v.] , born in 1607, was educated at Eton and Magdalen College, Oxford. He succeeded to the earldom on his father's death on 10 Nov. 1624, and inherited large property in London as well as in Hampshire. He owned the manor of Bloomsbury, besides Southampton House in Holborn. From Oxford he proceeded to the continent, and stayed for nearly ten years in France and the Low Countries. He married in France in August 1634, and soon afterwards returned home. In August 1635 he suffered serious anxiety from the persistency with which the king and his ministers laid claim in the name of the crown to his property in the New Forest about Beaulieu. In October 1635 a forest court, sitting under the Earl of Holland at Winchester, issued a decree depriving him of land worth 2,000l. a year. The earl petitioned for relief, and nine months later the king agreed to forego the unjust seizure of the property.

A man of moderate views, Southampton resented warmly the king's and the Earl of Strafford's extravagant notions of sovereignty. He was reluctant to identify himself with the champions of popular rights; but the close friendship, however, which had subsisted between his own father and the father of the third Earl of Essex inclined him to act with the latter when the differences between the king and parliament first became pronounced. During the Short parliament of 1640, he declared himself against the court, and in April voted in the minority in the House of Lords which supported the resolution of the House of Commons that redress of grievances should precede supply. But he went no further with the advanced party of the House of Commons. Although he had little sympathy with Strafford, he disliked the rancour with which the House of Commons pursued him. He dissociated himself from Essex when criminal proceedings were initiated against Strafford, and the estrangement grew rapidly. On 3 May 1641 he declined assent to Pym's ‘protestation against plots and conspiracies.’ This was signed by every other member present in each of the two houses, excepting Lord Robartes and himself. The commons avenged Southampton's action by voting that ‘what person soever who should not take the protestation was unfit to bear office in the church or commonwealth.’ Thenceforth Southampton completely identified himself with the king. He was soon appointed a lord of the king's bedchamber, and joint lord lieutenant for Hampshire (3 June 1641), and next year became a member of the privy council (3 Jan. 1641–2). He became one of the king's closest advisers, and remained in attendance on him with few intervals till his death. He accompanied Charles on his final departure from London in the autumn of 1641, but was hopeful until the last that peace would be easily restored. No sooner had Charles I set up his standard at Nottingham than Southampton prevailed on him to propose a settlement to the parliament. On 25 Aug. 1642 the king sent him and Culpepper to Westminster to suggest a basis for negotiation, but the parliament summarily rejected the overture. The king entrusted to Southampton the chief management of the fruitless treaty with the parliamentary commissioners at Oxford in 1643. Whitelocke says that the earl stood by the king daily during the progress of the negotiations, whispering him and advising him throughout. In the succeeding year he was appointed a member of the council for the Prince of Wales. On 17 Dec. 1644 Southampton and the Duke of Richmond, after receiving a safe-conduct from the parliament, again brought to Westminster a letter, in which Charles requested the houses to appoint commissioners to treat of peace. In January 1645 Southampton, whose efforts for peace never slackened, represented the king at the abortive conference at Uxbridge. Later in the year Southampton again pressed on the king the urgent need of bringing the war to an end. In April 1646 the king sent him and the Earl of Lindsay to Colonel Rainsborough, who was attacking Woodstock, with instructions to open negotiations through the colonel with the army. On 24 June 1646 Southampton was one of the privy councillors who, on behalf of the king, arranged with Sir Thomas Fairfax for the surrender of Oxford.

Before Southampton left Oxford a hasty rebuke from Prince Rupert led to a quarrel between the prince and Southampton, which led Rupert to send Southampton a challenge. Southampton chose to fight on foot with pistols. Sir George Villiers was appointed his second, but after all arrangements had been made for a duel the friends of the parties intervened and effected a reconciliation. In October 1647 Southampton, with the Duke of Richmond, Marquis of Ormonde, and others, ‘came to the king at Hampton Court, intending to reside there as his council,’ but the army vetoed the arrangement (WHITELOCKE, ii. 219). On 12 Nov. 1647 the king visited the Earl of Southampton at his house at Titchfield, on his way to the Isle of Wight, and Southampton followed the king thither. He afterwards claimed to have been the first to show the king at Carisbrooke the ‘Eikon Basilike;’ he affirmed that the book was written by Dr. Gauden and merely approved by Charles I ‘as containing his sense of things.’ In March 1648 he refused to assist in a new negotiation between the king and the independents. He was in London during the king's trial, and visited him after his condemnation. It is said that on the night following Charles's execution Southampton obtained leave to watch by the dead body in the banqueting hall at Whitehall, and that in the darkness there entered the chamber a muffled figure who muttered ‘Stern necessity.’ Southampton affirmed his conviction that the visitor was Cromwell. On 8 Feb. 1649 Southampton attended the king's funeral at Windsor.

After the king's death Southampton lived in retirement in the country. The parliament seems to have shown leniency in their treatment of his estate. He was allowed to compound for his ‘delinquency in adhering to the king’ by a payment on 26 Nov. 1646 of 6,466l., that sum being assumed to be a tenth of the value of his personal property. At the same time he was required to settle 250l. a year on the puritan ministry of Hampshire out of the receipts of the rectories in the county, the tithes of which he owned (Cal. Committee for Compounding, pt. ii. pp. 1507–8). His fortune was therefore still large, and he was liberal in gifts to the new king Charles and his supporters. After the battle of Worcester he offered to receive the prince at his house and provide a ship for his escape. He declined to recognise Cromwell and his government. When the Protector happened to be in Hampshire he sent the earl an intimation that he proposed to visit him. Southampton sent no reply, but at once withdrew to a distant part of the county. He corresponded with Hyde, with whom he had formed a close friendship at Oxford, and looked forward with confidence to the Restoration. When it arrived Southampton re-entered public life. His moderate temper gained him the ear of all parties. In the convention parliament he spoke for merciful treatment of the regicides who surrendered (LUDLOW, ii. 290). At Canterbury, on his way to London, Charles II readmitted him to the privy council and created him K.G. On 8 Sept. 1660 he was appointed to the high and responsible office of lord high treasurer of England. This office he held till his death.

On 5 Feb. 1660–1 Southampton publicly took possession of the treasury offices (PEPYS, i. 341). Next year he endeavoured to settle the king's revenue on sound principles, and to ‘give to every general expense proper assignments’ (PEPYS, ii. 427). At the same time he acted on the committee for the settlement of the marriage of the king with Catherine of Braganza. He scorned to take personal advantage of his place, as others had done, and came to an agreement with the king by which he was to receive a fixed salary of 8,000l. a year. The offices, which had formerly been sold by the treasurer for his own profit, were placed at the disposal of the king. So long as he held the treasurership no suspicion of personal corruption fell on him. But it was beyond his power to reduce the corrupt influences which dominated Charles II's personal following. Like his close friends Clarendon and Ormonde, who had also been councillors of the new king's father, he retained the decorous gravity of manner which had been thirty years before in fashion at Whitehall, and was wholly out of sympathy with the depraved temper of the inner circle of the court. He at first hoped that he might be able to reform the conduct of the king and his friends, or at least set a limit on their wasteful expenditure of the country's revenue. According to Clarendon he lost all spirit for his work when he perceived that it was out of human power to ‘bring the expense of the court within the limits of the revenue.’ He spoke with regret of his efforts in behalf of the king during the exile, and openly stated that, had he known Charles II's true character, he would never have consented to his unconditional restoration. Clarendon credits him with suggesting the sale of Dunkirk to meet the pressing needs of the exchequer; but his resentment of the king's behaviour, and his personal sufferings from the gout and stone, gradually withdrew him from active work in his office. He left the whole conduct of treasury business to his secretary, Sir Philip Warwick [q.v.] . In 1664 Lord Arlington, Ashley, and Sir William Coventry appealed to the king to displace Southampton, on the ground that he had delegated all his functions to Warwick. Clarendon, who constantly sought his advice, and was proud of the long intimacy, urged him to remain at his post and persuaded the king to retain his services. According to Burnet the king stood ‘in some awe of him, and saw how popular he would grow if put out of his service, and therefore he chose rather to bear with his ill humour and contradiction than to dismiss him.’

In church matters Southampton powerfully supported the principles of the establishment. In 1663 he opposed in council and parliament the bill for liberty of conscience, by which Charles proposed to allow a universal toleration of catholics. When the bill was presented to the House of Lords for the first time, Southampton declared that it was a ‘design against the protestant religion and in favour of the papists.’ On the second reading he denounced it as ‘a project to get money at the price of religion.’ Finally the bill was dropped.

When some troops of guards were raised on the occasion of the outbreak of the Fifth-monarchy men under Thomas Venner, Southampton strongly pronounced against a standing army. He declared ‘they had felt the effects of a military government, though sober and religious, in Cromwell's army; he believed vicious and dissolute troops would be much worse; the king would grow fond of them; and they would quickly become insolent and ungovernable; and then such men as he must be only instruments to serve their ends’ (BURNET).

Towards the close of 1666 Southampton fell desperately ill. A French doctor gave him no relief. ‘The pain of the stone grew upon him to such a degree that he resolved to have it cut; but a woman came to him who pretended she had an infallible secret of dissolving the stone, and brought such vouchers to him that he put himself into her hands. The medicine had a great operation, though it ended fatally.’ He bore the tedious pain with astonishing patience, and died at his house in London on 16 May 1667. He was buried at Titchfield.

Southampton's delicacy of constitution was a main obstacle in his career, and prevented his moderating influence from affecting the course of affairs to the extent that his abilities, honesty, and courage deserved. ‘Having an infirm body, he was never active in armes,’ wrote Sir Edward Walker (Ashmole MS. 1110, f. 170). Burnet described him as ‘a man of great virtue and of very good parts; he had a lively apprehension and a good judgment.’ According to his admiring friend Clarendon, ‘he was in his nature melancholick, and reserved in his conversation. … His person was of a small stature; his courage, as all his other faculties, very great’ (CLARENDON, Life, iii. 785). ‘There is a good man gone,’ wrote Pepys, who called at the lord treasurer's house just after his death; but, despite his integrity, Pepys was inclined to attribute to his slowness and remissness a large share in the disasters which fell on the nation during Charles II's reign. ‘And yet,’ Pepys added, ‘if I knew all the difficulties that he hath lain under, and his instrument Sir Philip Warwick, I might be brought to another mind’ (PEPYS, Diary, ed. Wheatley, vi. 321–2). Pepys always found him, officially, ‘a very ready man, and certainly a brave servant of the king;’ the only thing that displeased the diarist in him personally was the length to which he let his nails grow (ib. iii. 351).

He married three times. His first wife was ‘la belle et vertueuse Huguenotte,’ Rachel, eldest daughter of Daniel de Massue, seigneur de Ruvigny, whom he married in France in August 1634; she died on 16 Feb. 1640. By her Southampton had two sons, Charles and Henry, who died young, and three daughters—Magdalen, who died an infant; Elizabeth, wife of Edward Noel, first earl of Gainsborough; and Rachel, wife first of Francis, lord Vaughan, and secondly of William, lord Russell, ‘the patriot.’ Southampton's second wife was Elizabeth, eldest daughter and heiress of Francis Leigh, lord Dunsmore (afterwards earl of Chichester), by whom he had four daughters; only one survived youth, namely Elizabeth, who married, first (23 Dec. 1662), Josceline Percy, eleventh earl of Northumberland; and secondly (24 Aug. 1673), Ralph Montagu, duke of Montagu [q.v.] . Southampton's third wife was Frances, second daughter of William Seymour, second duke of Somerset [q.v.] , and widow of Richard, second viscount Molyneux of Maryborough in Ireland. His widow married, as her third husband, Conyers D'Arcy, second earl of Holdernesse; she was buried in Westminster Abbey on 5 Jan. 1680–1.

On his death without male heirs the earldom became extinct, but it was re-created on 3 Aug. 1670 in behalf of Charles Fitzroy, natural son of Charles II by the Duchess of Cleveland. The re-created earldom of Southampton was elevated into a dukedom on 10 Sept. 1675.

Southampton left his mark on London topography. In early life he abandoned the family mansion, Southampton House in Holborn. In 1636 he petitioned the House of Lords for permission to demolish it, and to build small tenements on its site. Permission was refused at the time, but about 1652 the earl carried out his design, and the old Holborn house was converted into Southampton Buildings. At the same time he built for himself a new and magnificent residence on the north side of what is now Bloomsbury Square. The new edifice, Southampton House, occupied the whole of the north side of the present Bloomsbury Square. It is supposed to have been designed by John Webb, Inigo Jones's pupil. The gardens included the south side of what is now Russell Square. Pepys walked out to see the earl's new residence on Sunday, 12 Oct. 1662, and deemed it ‘a very great and a noble work’ (PEPYS, Diary, iv. 256). Evelyn, who records a dinner on 9 Feb. 1665 at ‘my lord treasurer's’ in Bloomsbury, says that the earl built ‘a noble square or piazza, a little tower, some noble rooms, a pretty cedar chapel, a native garden to the north with good air.’ The house, Evelyn added, stood ‘too low.’

Much of the earl's landed property in both London and Hampshire passed, on Southampton's death, to his eldest daughter Elizabeth and her husband, Edward Noel, first earl of Gainsborough. On their only son dying without issue the Titchfield estate ultimately passed to their two granddaughters, co-heiresses—Elizabeth, wife of William Henry Bentinck, first duke of Portland, and Rachel, wife of the first duke of Beaufort. Titchfield House eventually became the property of the Duchess of Portland, whose husband assumed the secondary title of Marquis of Titchfield. The Titchfield property was sold by the third duke of Portland at the end of the eighteenth century.

Southampton's second daughter, Rachel, wife of William, lord Russell, and mother of Wriothesley Russell, second duke of Bedford, finally inherited the greater part of Southampton's property in London, the Bloomsbury estate falling to her on the death of her elder sister, the Countess of Gainsborough, in 1680. Southampton House in Bloomsbury descended to her son, the second duke of Bedford, and was renamed Bedford House; it was pulled down in 1800. The Bloomsbury property of the dukes of Bedford thus reached them through William lord Russell's marriage with Southampton's daughter Rachel. The memory of its original connection with the Earl of Southampton survives in the name of Southampton Row.

The Holborn property and the estate of Beaulieu in Hampshire fell to Elizabeth, duchess of Montagu, Southampton's daughter by his second wife.

A portrait of Southampton by Sir Peter Lely is the property of the Duke of Bedford at Woburn Abbey; it is reproduced in Lodge's ‘Portraits’ (v. 179). Another portrait belongs to the Duke of Portland at Welbeck Abbey. A third portrait, formerly in the Earl of Clarendon's gallery, has long since disappeared.

Sources

Clarendon in the Continuation of his Life gives an admirable sketch of his friend's career and character, 1759, vol. iii. pp. 780–90. See also Whitelocke's Memorials; Ludlow's Memoirs, 1625–72, ed. C. H. Firth, 1894; Burnet's Hist. of his own Time; Cal. State Papers, Dom.; Pepys's Diary, ed. Wheatley; Ranke's Hist. of England, vi. 84; Lodge's Portraits, v.; Wheatley and Cunningham's London Past and Present; Gardiner's Hist. of England, viii. 86, ix. 109, and Hist. of the Great Civil War.

Visitors may consult content provided by Oxford Publishing Limited for research and study purposes only. Any further use, including, but not limited to, unauthorized downloading or distribution of images or editorial content is strictly prohibited. Visitors must contact the Oxford Publishing Limited (facilitated by PLSclear) at plsclear@pls.org.uk.