Henry Wriothesley

1573-1624

A favourite of Elizabeth I, Henry Wriothesley became earl and ward of the state two days before his eighth birthday. A lover of literature, he was Shakespeare's sole dedicatee and purported patron, making possible some of the greatest plays and poems ever penned.

Visitors may consult content provided below by Oxford Publishing Limited for research and study purposes only. Any further use, including, but not limited to, unauthorized downloading or distribution of images or editorial content is strictly prohibited. Visitors must contact the Oxford Publishing Limited (facilitated by PLSclear) at plsclear@pls.org.uk .

Wriothesley, Henry, third earl of Southampton (1573–1624), courtier and literary patron, was born at Cowdray House near Midhurst in Sussex on 6 October 1573. He was the third child and only surviving son of Henry Wriothesley, second earl of Southampton (bap. 1545, d. 1581), and his wife, Mary Browne (b. in or before 1552, d. 1607), daughter of the first Viscount Montague. His parents had a stormy marriage, and when the boy was six they separated, largely because the father—a fervent Catholic who had spent eighteen months confined in the Tower of London—accused his young wife of adultery with a commoner named Donesame. In a long, rambling, somewhat incoherent letter to her father, the countess claimed that as for 'donesame his coming hither' for a secret tryst at the family's Dogmersfield estate, this could 'never' be proved (Akrigg, 14), but her husband was obdurate, unforgiving, and convinced of his own rightness. Serving as a go-between for his difficult parents, the young Henry Wriothesley carried a letter from the countess to his father, after which he was forbidden to see his mother.

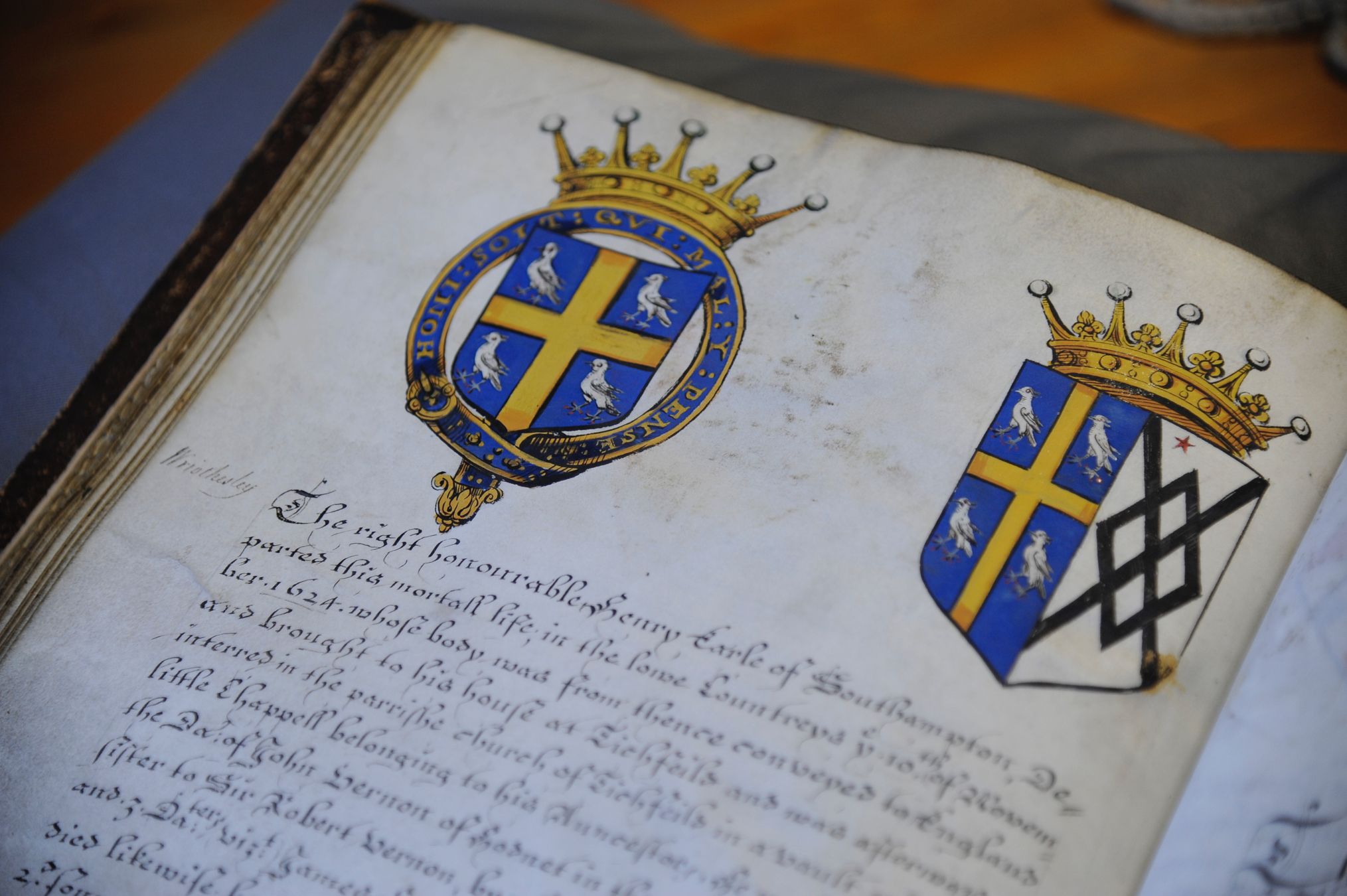

The angry second earl, according to Father Foley, went briefly to prison again for his Catholic practices in consequence of the anti-recusancy act of 16 January 1581 (Foley, 3.659). That ordeal worsened his already uncertain health, and two days before his son's eighth birthday, the father died: thus on 4 October 1581 the boy became third earl of Southampton. The troubled state of his parents' marriage, the boy's enforced separation from his mother, and no doubt what he had heard said about her, contributed to Southampton's early distrust of women, and for years he was to turn primarily to men for stimulus or affection. He did not come to be on easy terms with his mother, who remained a widow during nearly all of his minority; but on 2 May 1594 she married Sir Thomas Heneage, vice-chamberlain of the royal household, who died within a year, and in 1598 she took as a third husband a man younger than herself, Sir William Hervey, who had seen army service in the Lowlands and is sometimes thought to be the ‘M W. H.’ in Thomas Thorpe's dedication to Shake-Speares Sonnets (1609). Southampton's mother died in November 1607.

Formal training

Upon his father's death Southampton became a royal ward. For the time being or until his maturity, his landed property was held in trust by Lord Howard of Effingham, and custody of the young earl along with power to arrange his marriage fell to his guardian, Lord Burghley, who besides being the queen's powerful lord treasurer was also master of the wards. Despite his administrative life, Burghley maintained with the help of expert tutors, at his Cecil House in London's Strand, a brilliant educational establishment for young noblemen: it has been called 'the best school for statesmen in Elizabethan England' (Hurstfield, 255). Here Southampton received a sound training in Latin, history, and literature, and heard something about government, politics, and modern Europe. Book-loving, full of wise sayings, and pleased to dine with his wards, Burghley must have contributed to Southampton's love of literature. One advantage of being at Cecil House was that the young earl had a chance to meet others destined to rise to power in affairs of the state, including perhaps his future hero, the earl of Essex, who, at fifteen or sixteen, may have visited from his residence in Wales.

At the age of twelve in the autumn of 1585, Southampton was admitted to St John's College, Cambridge, where as a young nobleman he merited special attention and help. Early in the next year the college acquired a new, scholarly master, Dr William Whitaker, a man of mildly puritan sympathies, but St John's was chiefly run by Whitaker's assistant, John Alvey, a keen-minded puritan. The protestant training which Southampton received at Cecil House and at Cambridge firmly offset the Catholic atmosphere he had known in his father's home. At St John's there were lectures on topics such as Greek, arithmetic, geometry, or cosmography, and many students read both modern and ancient history; but much of Southampton's education focused on theology, ethics, and the oral and written presentation of arguments. In the summer Burghley kept up the argumentative emphasis by giving him Latin themes to write. Two of these survive, and although neither is very logical, Southampton lets his heart speak for him. The first theme, written in June 1586, replies to the topic, 'The arduous studies of youth are agreeable relaxations in old age'. The essayist believes that old age is 'often' wretched, but that 'young men may, with justice, relax their minds and give themselves up to enjoyment'. He quotes Cicero on youth's need for more freedom and on the wisdom of letting desire and passion sometimes 'triumph over reason' (BL, Lansdowne MS 50, fol. 51). Whatever Burghley felt about that, he knew the earl would have complex estates to manage and might benefit from legal training. By the time Southampton, at sixteen, had his MA degree at Cambridge in 1589, he was admitted at Gray's Inn. Burghley hardly wished him to neglect language and literature, and in any case the earl preferred the arts. Southampton soon had in his 'pay and patronage' John Florio, as a hot-tempered, gifted Italian tutor. According to Florio, the earl acquired such skill with Italian that he had no need to travel abroad to polish his mastery of the tongue, and Florio's Italian–English dictionary later includes the earl as one of its three dedicatees. The inns of court were filled with a good many idle, fashionable young men concerned with dancing, fencing, or the theatre, rather than with legal statutes; and the comely earl hardly had much time for the law himself. Significantly, he can be traced at Gray's Inn at a holiday time when skits, satires, and plays were performed, but there is little sign that he acquired much technical knowledge of litigation.

Sexuality and early reputation

In 1589 Burghley noted the birthdays of the royal wards and observed that the earl was approaching a marriageable age. For Southampton, he had a bride ready. Burghley decided to marry him to his own granddaughter, Lady Elizabeth Vere (1575–1627), who at twelve had lost her mother, Anne, and appeared to be neglected by her father, the seventeenth earl of Oxford. Such an alliance with a famous, staunchly protestant family might have cleared Southampton of a papist taint. His mother was guilty of Catholic indiscretions, most of them minor, as when she tried to clear an 'olde poor woman', charged it seems with recusancy (Folger, MS L. b. 338); and his father's link with a regicidal plot had led to the Tower. Yet despite pressure by July 1590, the earl refused to be wed, though Burghley found allies for the wedding plan in the earl's mother and grandfather. In resisting his guardian, the earl incurred more than Burghley's mere displeasure, since the law held that if a ward would not marry at his lord's request, on coming of age he must pay him what anyone would have given for the marriage. Southampton thus faced paying an enormous fine, said to be £5000, on turning twenty-one in October 1594. Living on a moderate allowance, he had begun to show a plucky, defiant spirit.

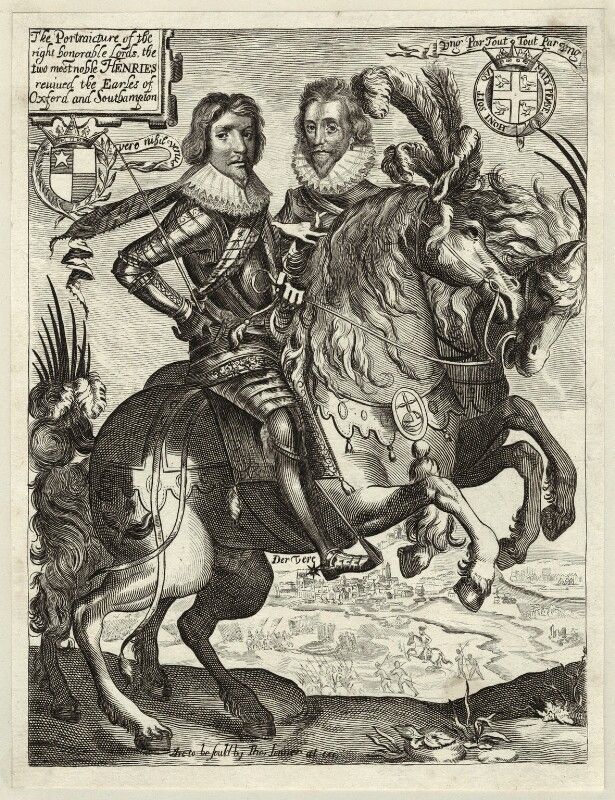

Also he had begun to attract many admirers. Southampton made of himself an exhibit,and his image survives in more contemporary portraits than anyone else's but the queen's. As a young man he was strikingly attractive, with nearly feminine features, bright blue eyes, and a soft, alluring gaze to match his sweetly toned voice. He was to show off his lightly built, slender form with costly, clinging fabrics such as a white silk doublet, and strike poses with his dancing hat-feathers, his purple garters, and his long auburn hair with one tress falling to the breast. Was he homosexual or bisexual? Thoseterms were then unknown, and Southampton's sexual proclivities are difficult to discover. A Tudor male was not thought of as being unalterably defined by his sexual preferences, even if he had a male lover or a ‘Ganymede’. William Reynolds, a less than reliable witness who expected to be believed, wrote later that when in Ireland, Southampton slept in a tent with his brother officer, Piers Edmondes, and 'the earle Sowthamton would cole and huge [embrace and hug] him in his armes and play wantonly w[ith] him' (BL, MS M/485/41). Among the earl's closest friends were the brothers Sir Charles and Sir Henry Danvers, neither of whom married; and Thomas Nashe complimented Southampton, somewhat ambiguously, in the dedication of The Unfortunate Traveller in 1594: 'A dere lover and cherisher you are, as well of the lovers of Poets, as of Poets themselves'. Yet the earl did not remain a bachelor. In the mid-1590s Southampton became involved with one of the queen's maids of honour, the demure Elizabeth Vernon, daughter of John Vernon of Hodnet, Shropshire, and a cousin of Robert Devereux, second earl of Essex. Born on 11 January 1573, she was a few months older than Southampton who for a while broke off their relationship, but married her hastily in August 1598.

Just before he turned twenty-one the young Cambridge graduate had the appeal of an androgynous icon and a potentially great patron. Sir Philip Sidney's death in 1586 had left room for a new inspirer, a symbol of high attainment in art and war. Southampton was manly enough to hope to fight in battle, but attractive enough to elicit delicate verses. Noting his attendance with the queen at Oxford, John Sanford in a Latin poem claimed that no one present was more comely, 'though his mouth yet blooms with tender down' (Apollinis et musarum euktika eidyllia, 1592). In the same year a poem of fifteen pages in Latin entitled Narcissus, by his guardian's secretary John Clapham, was dedicated to the young earl. A group of writers loyal to Essex and Southampton formed around them, and by the time Gervase Markham and Barnabe Barnes, in new sonnets, had praised Southampton's bright eyes and lovely voice, he had attracted the greatest poet of all.

Shakespeare's patron

Just when and how the earl first met Shakespeare are not clear, but they had acquaintances in common. Southampton attended the royal court with the younger Fulke Greville, whose father at Stratford had known a board of aldermen which included the dramatist's father. Young Fulke Greville could have put the earl in touch with Shakespeare, but it is just as possible that keen, au courant playgoers at Gray's Inn did. Except for small respites, bubonic plague kept London's theatres shut for almost two years starting in mid-1592, and it was in this period that Shakespeare sought the help of a fashionable patron. Ironically, Southampton had little but enthusiasm to offer any poet. He hardly had funds to spare; he lived on a fixed allowance and faced paying a gigantic fine to Burghley, plus another vast sum to get his estates out of wardship. After he turned twenty-one in 1594, his need for money became desperate. In November of that year, he leased out part of Southampton House, and a few years later had to sell off five of his manors, including Portsea and Bighton.

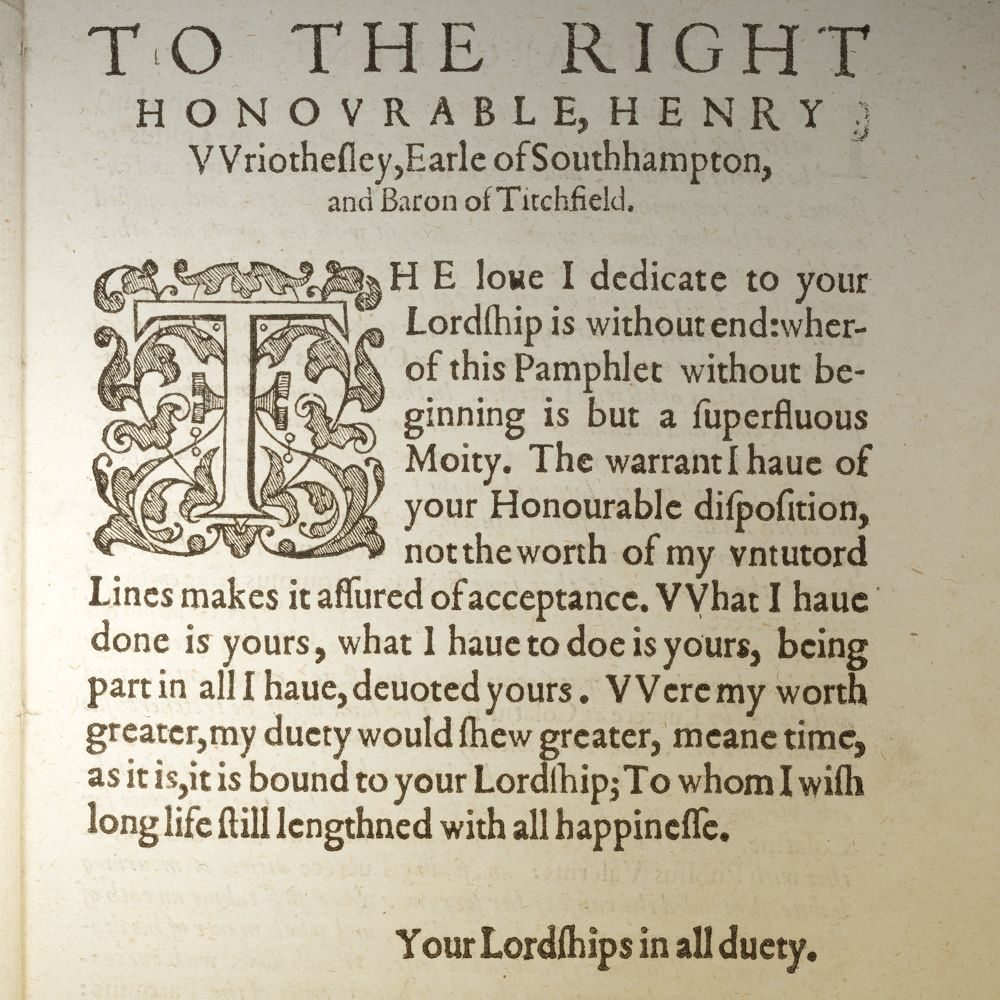

Shakespeare's use of the earl as a patron was of brief duration. His dedicatory letter printed in Venus and Adonis (soon after 18 April 1593) suggests that he barely knows the nineteen-year-old earl: 'I know not how I shall offend in dedicating' the present work, Shakespeare admits, though he hopes to offer 'some graver labour'. The graver labour was probably The Rape of Lucrece (printed in spring 1594), and despite the formality and hyperbole in his new letter to Southampton, prefacing the volume, Shakespeare's tone is more intimate and confident than the year before. His love for his patron is 'without end', he declares; and he adds, 'What I have done is yours, what I have to doe is yours'.

However, that pledge of loyalty was superseded by events. By the summer of 1594 Shakespeare had joined the Chamberlain's Men, a stable, lasting troupe which held his loyalty and saved him from needing the support of the earl's name or patronage. The myth that Southampton gave him £1000 is unfounded, and it is only a conjecture that Shakespeare was entertained at the earl's Titchfield estate where he perhaps found the name ‘Gobbo’ (for Shylock's servant) among local parishioners' names. Shakespeare was not ungrateful for the privilege of dedicating Venus and Adonis and Lucrece to a nobleman. His respect for the Essex-and-Southampton faction appears in his only clear, specific allusion to a contemporary, extra-dramatic event, when the Chorus in Henry V (v.o.29–35) refers to Essex's possibly victorious return from Ireland in 1599. Still later, Shakespeare agreed to devise an impresa for Southampton's close friend the sixth earl of Rutland.

Southampton may be involved in Shakespeare's sonnets, but a too-close connection is often supposed to exist between Tudor poets and patrons. In 1594 Shakespeare was casting off his allegiance to the earl; but there is no real likelihood that he traduced him by drawing his portrait as the fickle, treacherous Young Man of the sonnets, who is implicitly 'lascivious' (sonnet 95), 'sensual' to a 'fault' or to his 'shame' (sonnets 34, 35), and ridden with vices. The naïve notion that Southampton was Shakespeare's weak, lustful Young Man was first argued in 1817, when older sonnet conventions were often forgotten, and Tudor lyrics were mistakenly interpreted in the light of Romantic or Wordsworthian criteria such as directness, candour, and reportorial fidelity. Shakespeare mocked 'wailful sonnets' as early as Two Gentlemen of Verona (iii.ii.69); he played exuberantly on the name 'Will' in sonnets 135, 136, and 143, and had a wide, sophisticated knowledge of artful disguisings, games, and tricks of sonneteers of the early 1590s (Honan, 181–90). His sonnets were meant to elicit expert appreciation, but they are not literal reports, and though profoundly exploratory they do not sketch ‘real’ characters, scenes, or experiences as candidly as modern sonnets may. The Dark Lady is a composite portrait, which takes details from Sidney's seventh sonnet in Astrophil and Stella (1591), and no one has shown incontrovertibly that Shakespeare's sonnetcharacters had real models. Moreover, he had no need to risk his career, damage a company, or mortify a patron or the patron's friends by presuming to write intimately of the sexual habits of an earl. It is not clear that Southampton received any of these lyrics, and the few private friends who knew manuscript versions of some of them by 1598 were writers such as Francis Meres and Michael Drayton. The references to 'love'and 'duty' in the letter in The Rape of Lucrece have echoes in sonnet 26; but in his prose address and in that sonnet alike, Shakespeare draws on the commonplace literary language of courtly love. There is no sign that sonnet 26 was meant for Southampton, and its 'idiomatic overlap with the prose address is too slight to be in itself significant' (Kerrigan, 207).

Nevertheless, Southampton's comeliness and physical grace must have impressed Shakespeare, who received some 'warrant' of the earl's approval of Venus and Adonis as this is acknowledged in the dedicatory letter in Lucrece. Shakespeare may well have drawn upon his feelings for the earl without presuming to delineate him, but he cannot have intruded often in Southampton's set, or some notice of this would have survived; there is no sign that he mixed with the literati, or even with poets at the fringes of the earl's set such as Barnes, Markham, or Drayton. In all probability, Shakespeare's meetings with his patron were few. In urging a young man of high estate to marry, sonnets 1–17 seem to fit the earl's predicament in opposing Burghley's marriage plan. But these seventeen sonnets are artistic variations upon a theme, and in defying the conventions of courtly love they were meant to be admired, not to affect behaviour. It is unlikely that they were designed to brainwash Southampton into marrying, and one cannot be certain that the earl saw them. There are parallels between the earl's military career and the brief, fictive one of Bertram in All's Well that Ends Well, but the main outlines of Bertram's career come from Shakespeare's literary sources. The sonnet that is most likely to bear upon the earl is no. 107, if it relates to King James's accession and responds to his order, of 5 April 1603, to release Southampton from prison: 'Now with the drops of this most balmy time', wrote Shakespeare, 'my love looks fresh'. That he recalls his patron in 'my love looks fresh' is slightly strengthened by the fact that other verse-congratulations on Southampton's release from custody in 1603 were offered by Samuel Daniel and John Davies of Hereford.

Shakespeare's sonnets differ from those of other Tudor sonneteers partly in an indefiniteness, or in an unresolved attitude to half-truths, lies, and self-deceptions in human relationships which his lyrics explore, and the earl offered him, at best, a hypothetical object of a poet's 'love', or an ideal to be tested. In his later-written sonnets, he may take as much from his acquaintance with another elegant patron, William Herbert, third earl of Pembroke, but, again, without necessarily using him as a model or assuming intimacy with the feelings of a living nobleman. There is no reason to think that either patron would have recognized himself in the volume of Shakespeare's sonnets printed by Thorpe in 1609.

Public and private life, 1595–1603

At twenty, Southampton was mentioned for nomination as a knight of the Garter, and although he was not chosen, the mention was a high compliment. Two years later, on 17 November 1595, he distinguished himself in the lists set up in Queen Elizabeth's presence in honour of the thirty-seventh anniversary of her accession, and was likened by George Peele, in his account of the scene in his 'Anglorum feriae', to Bevis of Southampton, an ancient model of chivalry. Nashe penned for either the young earl or Lord Strange a bawdy poem entitled 'The Choise of Valentines', which opens and closes with a sonnet to ‘Lord S.’. Yearning for a military career, the earl was honoured in 1595 by a sonnet in which Gervase Markham inscribed to him a patriotic poem on Sir Richard Grenville's fight off the Azores. In 1596 Southampton finally proved himself as a volunteer with his friend Essex in the military and naval expedition to Cadiz. The next year he again accompanied Essex on the expedition to the Azores.

These experiences developed in him a martial ardour which improved his position, but on his return to court in January 1598 he gave some proof of an impetuous temper. One evening in that month Sir Walter Ralegh with Southampton and a courtier named Parker were playing at primero in the presence chamber, but when Ambrose Willoughby, an esquire of the body, requested them to desist on the monarch's withdrawal to her bedchamber, Southampton struck Willoughby, and during a scuffle the esquire pulled off some of the earl's auburn locks. Next morning the queen thanked Willoughby for what he did. Later, in 1598, Southampton accepted a place in the suite of the queen's secretary, Sir Robert Cecil, who was going on an embassy to Paris. It was while in Paris that he learned that Elizabeth Vernon was pregnant, and hurrying home he secretly married her. Observers at court had thought Southampton too fantastic and volatile to take a wife, but his volatility was offset by a capacity for loyalty, and the marriage was a happy and enduring one. His wife bore him three daughters named Penelope (b. 1598), Anne, and Elizabeth, as well as two sons, James (b. 1605), and Thomas Wriothesley (1608–1667), who because of his brother's early death in 1624 succeeded to the family title and estates. Angry to learn that her maid of honour had been seduced and secretly wed, the queen in 1598 committed the bride to one of the least unpleasant lodgings in the Fleet, where Southampton was ordered to join her on his return from France. He and his wife were soon released from gaol, but he never recovered Elizabeth's favour.

Seeking employment in war, Southampton set out for Ireland in March 1599 with his friend Essex, the lord deputy, who nominated him general of the horse, though the queen refused to confirm this appointment. The young earl fought well in minor skirmishes, but by the autumn he was back idling in London where, with the fifth earl of Rutland, he saw 'plays every day' (Collins, 2.132). A real tragedy was then at hand. When Essex was committed to custody after his return from Ireland, Southampton was drawn into a conspiracy whereby Essex and his friends aimed to recover by violence their influence at court. In July 1600 Southampton revisited Ireland in a futile attempt to recruit the lord deputy, Lord Mountjoy, for Essex's cause. On Thursday 5 February 1601 several friends of Essex persuaded actors at the Globe theatre to revive for the following Saturday a play that was probably Shakespeare's Richard II so as to incite the London public by presenting on stage the deposition of a king. On Sunday 8 February, a day after the performance, the rising failed completely. Arrested and sent to the Tower, Southampton was brought to trial with Essex on a capital charge of treason at Westminster Hall. Both defendants were condemned to death, but thanks to Sir Robert Cecil's argument that the younger earl was weakly led astray by his love of Essex, his own sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. Essex was beheaded on 25 February, and Southampton, stripped of his earldom, spent over two years in prison.

Later life, 1603–1624

Essex had been James's sworn ally, and one of the king's first acts on his accession to the crown of England was to set Southampton free in April 1603 and so enable him to resume his place at court. It was then that Samuel Daniel and John Davies offered congratulations on the earl's release in verse. On 2 July 1603 he was made KG. He was recreated earl of Southampton in the same month, and on 18 April 1604 was fully restored to his former rights by an act of parliament. The king not only appointed Southampton captain of the Isle of Wight and Carisbrooke Castle, as well as bailiff of royal manors on the island, but granted him the manors of Romsey in Hampshire, Compton Magna in Somerset, and Dunmow in Essex. He also awarded him the farm of the customs on sweet wines, not only a financially lucrative concession but a highly symbolic gesture, given that the farm had previously belonged to Essex. He became one of the two lord lieutenants of Hampshire on 10 April 1604, and commissioner for the union with England on 10 May. The new queen showed him special favour; he became her master of the game, and other old allies of Essex were given places at her court. In 1603 he entertained her at Southampton House, where Shakespeare's players acted Love's Labour's Lost in her presence. The earl was a steward at the magnificent entertainment given at Whitehall on 19 August 1604 in honour of the signing of a treaty of peace with Spain, and twice danced a coranto with the queen.

But Southampton's impetuosity had not diminished. In July 1603, in the presence chamber, when the queen expressed astonishment that so many great men had done so little for themselves on the day of Essex's uprising, Southampton said that their opponents falsely had made the attempt look like a treasonous attack on Queen Elizabeth's person. Had it not been for that, he added, Essex's opponents would not have dared to put down the revolt. Lord Grey, an old enemy of Southampton and an opposer of Essex, was standing by, and, imagining himself aimed at, retorted that the daring of Essex's opponents was not inferior to that of his friends. Southampton gave the interlocutor the lie direct, and was afterwards ordered to the Tower for infringing the peace of the palace. Tension between the privy council and the bedchamber officers limited Cecil's room for manoeuvre and the opportunity fully to integrate Southampton and the Essex party into the court.

Southampton used his following in the Commons in the parliament of 1604 to support Cecil's plans for a permanent tax to support the crown, in return for the surrender of the right of wardship, while opposing (like Cecil) the king's plan for a union with Scotland. Southampton's parliamentary allies—principal among them being Sir Edwin Sandys, Sir Herbert Croft, Sir Maurice Berkeley, and Sir Henry Neville—successfully argued before the Lords and judiciary that James's measure, intended to proceed on the assumption that the union was already complete in his person, would extinguish English identity and common law and was therefore illegal. When the taxation scheme was rejected by the Lords—led by Southampton's opponent Henry Howard, earl of Northampton—on the grounds that it was injurious to the royal prerogative, James sought to relieve the deadlock by arresting Southampton and some of his party from the Lords and Commons on 24 June 1604. They were charged with pro-Catholic and anti-Scottish conspiracy, and Southampton's table talk against the union and the bedchamber was cited as evidence. Southampton and his friends were released within days 'to please the parliament' (Cuddy, 129); the incident strengthened Cecil's usefulness to the king as a parliamentary manager, as it demonstrated the limits of royal authority, and Southampton's position as patron of a large proportion of Cecil's support in the Commons. Throughout the first few years of James's reign Southampton's party's defence of parliamentary right in issues relating to finance and the naturalization of the Scots contributed to tension between the Commons, Cecil and James, and probably also to an uneasy relationship between Cecil (earl of Salisbury from 1605) and Southampton.

Southampton's faction continued to oppose enhancement of the royal prerogative through the crisis over purveyance, wardship and extra-parliamentary impositions in the 1610 parliament. Southampton's dislike of noblemen who derived their eminence from their positions at court alone may lie behind his violent quarrel with the earl of Montgomery at tennis in 1610, but his alliance that year with James's new favourite Sir Robert Carr may have led to his acting as carver to Prince Henry at his creation as prince of Wales, to the pleasure of the king.

Following the death of Salisbury in 1612 it was predicted that Southampton would succeed him as lord treasurer with Sir Henry Neville becoming secretary of state, in alliance with a bedchamber led by Carr. James was not convinced by the proposal of Southampton and Neville that royal government should rely on parliamentary support, and instead encouraged Carr to look towards Northampton and the Howards, who instead emphasized the prerogative. Carr—from 1613 earl of Somerset—turned again to Southampton in the parliament of 1614, but the alliance was weakened by the successful exploitation by Northampton of the suspicion new MPs felt for the alliance of the Southampton group with Somerset, and the Commons was paralysed. Southampton then broke with Somerset and led a party in the Lords that sought to meet formally with Sandys and the leaders of the Commons in order openly to oppose further extra-parliamentary taxation as inevitably leading to tyranny. The 'addled' parliament was dissolved in disarray and with James furious; but Somerset was also vulnerable, and Southampton supported the earl of Pembroke and other better-placed courtiers in the promotion of George Villiers as a new favourite.

Excluded from meaningful office, Southampton devoted much of his leisure and ample wealth during this period to organizing colonial enterprise. He helped to equip Weymouth's expedition to Virginia in 1605, and became a member of the Virginia Company's council in 1609. He was admitted a member of the East India Company in the same year. In April 1610 he helped to dispatch Henry Hudson to seek the north-west passage, and he was an incorporator both of the North-West Passage Company in 1612 and of the Somers Island Company in 1615. He was chosen treasurer of the Virginia Company on 28 June 1620, and retained office until the company's charter was declared void on 16 June 1624. Southampton exhibited skill as well as unexpected tact in the company's troubled final months, since he kept the good favour of the king and shareholders alike. On 19 November 1623 the company granted him twenty shares of land in the colony in recognition of his 'singular wisdome', care, industry, and 'unquestionable integritie' (Wriothesley papers, 312). The map of Virginia commemorates his labours as a colonial pioneer. Southampton hundred was named in his honour (17 November 1620), and the city of Hampton and its adjacent harbour of Hampton Roads took their name from what was originally known as the Southampton River.

Southampton's political fortunes showed signs of recovery when he accompanied James I on a long visit to Scotland in 1617. In 1619 Southampton was nominated a privy councillor by James, who was then seriously ill and believed to be close to death and anxious to provide his successor with the broadest feasible base. His parliamentary influence recommended him to Villiers, now an independent power and duke of Buckingham. He was sworn on 19 April 1619, but in the next few years he quarrelled with Buckingham, almost to the point of a fist fight in the House of Lords. Southampton opposed James's systematic sale of English peerages, initiated in 1614, as an attack on the customary role of the old nobility once defended by Essex; the sales were enthusiastically promoted by Buckingham, as were those of patents and monopolies. In the parliament of 1621 he supported the impeachment of Francis Bacon, sacrificed by the king and Buckingham for his role in certifying the offending transactions, and on 3 May not only supported a proposal to degrade him but asserted that he ought to be banished. On 16 June Southampton was arrested and confined to the house of John Williams, the lord keeper and dean of Westminster, on the charge of mischievous intrigues with members of the Commons. He was released a month later and ordered to repair to his own seat of Titchfield in the custody of Sir William Parkhurst, but only relieved from Parkhurst's restraint on 1 September.

Southampton was slow to acknowledge his real sympathies in religion. After his father died, he was head of one of the great Catholic families, but his protestantism became apparent when he married. His conversion has been credited both to the influence of Essex and to Edwin Sandys. Although engagingly spontaneous, he could be evasive and secretive. In youth he was self-indulgent, and it was partly because he spent so much on clothes, pleasures, and pastimes that he was strapped for funds until about 1597. His fondness for the theatre and for military service did not abate, and even in 1614 he had gone out as a volunteer to engage in the war in Cleves. Numerous works were dedicated to him, and over a dozen portraits of him survive. Having inherited an estate valued at £1097 6s. per annum, Southampton sold off some holdings, but acquired property after 1603, invested in the East India Company, and left an estate probably worth well over £1500 per annum at his death.

Last days and his significance

In 1622 Southampton came to a new arrangement with Buckingham, who adopted a protestant, anti-Spanish foreign policy in keeping with that advocated by Southampton and his allies. In the parliament of 1624 the Commons was managed by Southampton's friends Sandys and Sir Edward Coke, outlawing monopoly patents and enacting preventative measures against extra-parliamentary financial instruments, as well as voting subsidies towards involvement in the continental war. Southampton with his elder son, James, took command of a troop of English volunteers who meant to assist the Dutch in their campaign against Spain. After landing in the Low Countries, father and son were both attacked by fever. Young James died at Rosendael on 5 November. The exhausted, grieving earl accompanied his son's body to Bergen-op-Zoom, but there, on 10 November 1624, he himself died 'of a Lethargy', perhaps a heart attack (Akrigg, 174). He was survived by his wife, who was still alive in November 1655. Father and son were buried in the chancel of the church of Titchfield, Hampshire, on 28 December.

Opinions of Southampton have changed considerably in time. Gervase Markham offered a brief biography of him in a work entitled Honour in his Perfection (1624). Nathan Drake's Shakspeare and his Times (1817) supplied the first full argument for Southampton's identity with the hero of Shakespeare's sonnets. Absurd speculations about Shakespeare's relations with his patron reached a peak in the 1930s, but have been countered by G. P. V. Akrigg's first sixteen chapters in Shakespeare and the Earl of Southampton (1968) and also by later researches into historical contexts and the Tudor sonnet vogue. Southampton is accurately seen as a key, early promoter of colonizing in Virginia, and has emerged as a significant political figure of the reign of James I, inheriting the political following of his friend Essex, and in turn bequeathing a political faction to Essex's son. His passion for books and literature, which brought him into contact with Shakespeare, never diminished. Before King James's accession Southampton was seldom in a position to offer large sums of money or other tangible gifts to writers, though he aspired to be a significant patron of letters, and after his prospects improved he helped the universities. Thanks to his generosity, Oxford's new Bodleian Library in 1605 was able to buy over 400 books and manuscripts, including forty-eight texts in Spanish and a copy of the first edition of Cervantes' Don Quixote (Ungerer, 17). In late life the earl presented books and illuminated manuscripts worth £360 to furnish a new library at St John's College, Cambridge. Until his death, and even after it, he was the object of literary eulogies. Shakespeare, Drayton, Daniel, and others were indebted to his personal charm, talk, encouragement, or reputation in the 1590s. In early manhood, he symbolized artistic beauty and high aspiration for many Elizabethans, and helped to inspire some of their greatest lyric poetry.

-

G. P. V. Akrigg, Shakespeare and the earl of Southampton (1968)

-

Hants. RO, Wriothesley papers, MS 5M53

-

DNB

-

J. Hurstfield, The queen's wards (1958)

-

CSP dom., 1547–1625

-

W. Shakespeare, The sonnets and ‘A lover's complaint’, ed. J. Kerrigan (1986)

-

P. Honan, Shakespeare: a life (1998)

-

A. L. Rowse, Shakespeare's Southampton: patron of Virginia (1965)

-

G. Ungerer, ‘The earl of Southampton's donation to the Bodleian in 1605 and its Spanish books’, Bodleian Library Record, 16 (1997), 17–41

-

V. Traub and T. Braunschneider, ‘Recent studies in homoeroticism’, English Literary Renaissance, 30 (2000), 284–329

-

A. Bray, Homosexuality in Renaissance England (1995)

-

BL, MS M/485/41

-

BL, Lansdowne MS 50, fol. 51

-

H. Sydney and others, Letters and memorials of state, ed. A. Collins, 2 (1746), 132

-

H. Foley, ed., Records of the English province of the Society of Jesus, 3 (1878), 659

-

Folger, MS L. b. 338

-

T. Nashe, The unfortunate traveller (1594)J.

-

Sanford, Apollinis et musarum euktika eidyllia (1592)

-

N. Cuddy, ‘The conflicting loyalties of a “vulgar counselor”: the third earl of Southampton, 1597–1624’, Public duty and private conscience in seventeenth-century England: essays presented to G. E. Aylmer, ed. J. Morrill, P. Slack, and D. Woolf (1993), 121–50

-

GEC, Peerage, new edn, 12/1, 128–31

-

BL, MS M/485/41

-

Hants. RO, corresp. and papers, 5M53

-

Hunt. L., MS HA 13684

-

U. Nott. L., corresp.

-

BL, Harley MSS 570, 7000

-

BL, Lansdowne MSS 16, 37, 43, 50, 107, 627

-

Hatfield House, Hertfordshire, Cecil MSS, vols. 100–03, 164, 170

-

N. Hilliard, oil miniature, 1594, FM Cam.

-

oils, 1600, priv. coll., on loan to NPG; repro. in Rowse, Shakespeare's Southampton, facing p. 133

-

oils, 1610–1615, priv. coll.

-

S. de Passe, line engraving, 1617, BM

-

D. Mytens, oils, 1618, Althorp, Northamptonshire; version, NPG

-

I. Oliver, oil miniature, 1620; formerly owned by collector at Hamburg

-

P. van Somer, oils, 1621, Shakespeare Memorial Gallery, Stratford upon Avon; repro. in Rowse, Shakespeare's Southampton, facing p. 296

-

attrib. M. van Miereveldt, oils, priv. coll.

-

attrib. M. van Miereveldt, oils, Hardwick Hall, Derbyshire

-

P. Oliver, oil miniature; formerly owned by J. Whitehead

-

P. Oliver, oil miniature; formerly owned by F. Cook

-

oils, Buccleuch estates, Selkirk [see illus.]

-

oils, St John Cam.

-

oils; formerly owned by W. Digby

-

over £1500 p.a.; inherited lands est. £1097 6s. 0d. in 1582; spent lavishly and had many encumbrances; sold off five manors; later acquired at least three more; invested in East India Company; wealthy enough to finance expedition before death: Akrigg, Shakespeare and the earl of Southampton, 19–22, 38–9, 58–9, 69, 73, 165, and 175 n. 2

View the article for this person in the Dictionary of National Biography archive edition.

See also

-

Wriothesley, Henry, second earl of Southampton (bap. 1545, d. 1581), magnate

-

Wriothesley, Thomas, fourth earl of Southampton (1608–1667), politician

External resources

Bibliography of British and Irish history

Copyright © Oxford University Press 2019.

Printed from Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice). Subscriber: Cambridgeshire Libraries Archive & Info Service; date: 24 September 2019

Visitors may consult content provided by Oxford Publishing Limited for research and study purposes only. Any further use, including, but not limited to, unauthorized downloading or distribution of images or editorial content is strictly prohibited. Visitors must contact the Oxford Publishing Limited (facilitated by PLSclear) at plsclear@pls.org.uk.