Thomas Wriothesley 1505-1550

English peer, secretary of state, Lord Chancellor, privy counselor to Edward VI and Lord High Admiral. Thomas Wriothesley served as a loyal instrument of King Henry VIII in the latter's break with the Catholic church. He was one of the executors of Henry's will, and in accordance with the dead King's wishes, he was created Earl of Southampton on 16 February 1547.

Visitors may consult content provided below by Oxford Publishing Limited for research and study purposes only. Any further use, including, but not limited to, unauthorized downloading or distribution of images or editorial content is strictly prohibited. Visitors must contact the Oxford Publishing Limited (facilitated by PLSclear) at plsclear@pls.org.uk .

Entry by Michael A.R. Graves , Copyright © Oxford University Press 2019, Reproduced with permission of the Licensor through PLSclear, Published in print: 23 September 2004, Published in print: 23 September 2004, This version: 03 January 2008

Wriothesley, Thomas, first earl of Southampton (1505–1550), administrator, was the grandson of John Writhe, Garter king of arms, nephew of Sir Thomas Wriothesley, his successor, and cousin of Charles Wriothesley, who became Windsor herald. His father, William, like his brother Thomas, adopted Wriothesley as the family name. William, York herald, married Agnes, daughter of James Drayton of London, and they had four children. Thomas, the eldest son, was born on 21 December 1505, his sisters, Elizabeth and Anne (who married Thomas Knight of Hook in Hampshire), in 1507 and 1508, and his brother, Edward, in 1509. It was a sign of the family's rising status and fortunes that Edward Stafford, third duke of Buckingham, and Henry Percy, fifth earl of Northumberland, were godfathers at Edward's baptism.

Education, and early career in government

Thomas Wriothesley was first educated at St Paul's School, London, where his contemporaries included John Leland and William Paget. About 1522 he proceeded to Trinity Hall, Cambridge, where his fellow students again included Paget, while his teacher in civil law was Stephen Gardiner. All three had leading roles in one of Plautus's comedies, and the red-haired Wriothesley, noted for his looks, was praised for his performance. Leland, who appears to have been his friend from childhood, later wrote a tribute to his qualities of mind, integrity, and handsome appearance. Wriothesley did not, however, proceed to a degree, but instead pursued a career at the court of Henry VIII. In 1524, when only nineteen, he became a client of Thomas Cromwell, whom he styled his master and from that date many documents are in his handwriting. In 1529–30 he was clerk to Edmund Peckham, cofferer of the household; in 1530 he was king's messenger; and before 4 May 1530 he was appointed joint clerk of the signet under Stephen Gardiner, who was now the king's secretary. He remained in that post for a decade and during that time he also continued to serve Cromwell. Wriothesley carried out a wide range of administrative business and became known as an effective middleman. At the same time he began to experience the material benefits of office, for example the reversion of the office of bailiff in Warwick and Snitterfield, and an annuity of £5 from St Mary's, York.

In December 1532 Wriothesley was sent to Brussels with dispatches, and in the following October royal service took him to Marseilles. From there he complained to Cromwell that his 'apparel, and play sometimes, whereat he is unhappy, have cost him above 50 crowns' (LP Henry VIII, 6, no. 1306). It is probable, albeit uncertain, that these missions concerned Henry VIII's 'great matter', the annulment of his marriage to Katherine of Aragon. His services in this and in the dissolution of the monasteries gained Wriothesley the favour of the king, while at the same time Cromwell came to appreciate his intelligence, diligence, and managerial skills. Sometimes he was employed in politically sensitive matters, such as the examination of Lord Thomas Howard's love affair with Lady Margaret Douglas, or the destruction of St Swithin's shrine and the removal of all relics and treasure at Bishop Gardiner's cathedral in Winchester. He was also constantly busy as an administrator during the 1530s, not only as chief clerk of the signet but also as Cromwell's private secretary and his representative at the privy seal. He was 'manifestly the most successful civil servant of his day, in a way the head—not officially of course— of the civil service in the later 1530s' (Elton, 312).

King's Servant

By 1533 Wriothesley had married Jane (d. 1574), daughter and heir of William Cheney of Chesham Bois, Buckinghamshire, and Emma, daughter of Thomas Walwyn of Much Marcle, Herefordshire. She was also connected, presumably by parental marriage, to Stephen Gardiner and his private secretary and nephew, Germayne Gardiner, who was her half-brother. She died on 15 September 1574 and was buried at Titchfield. Thomas and Jane had three sons: William, who died in August 1537; Anthony, who died an infant c.1542; and Henry Wriothesley (bap. 1545, d. 1581), the only surviving son and successor. They also had five daughters: Elizabeth, Mary, Katherine, Anne, and Mabel. In 1534 Wriothesley was admitted to Gray's Inn, while in 1536 he was appointed engraver of the Tower mint (29 May) and constable (with Lord Sandys) of Donnington Castle (21 July). When the Pilgrimage of Grace erupted during that year, he attended Henry VIII at Windsor throughout the crisis, transmitting the king's fund-raising instructions to Cromwell. In October 1537 he informed Gardiner and Lord William Howard of Queen Jane Seymour's death and attended Prince Edward's baptism. Wriothesley the bureaucrat had also become the courtier. As such he enjoyed the material rewards which resulted from loyal service and royal favour. Between 1537 and 1547 he acquired, chiefly through royal grant, former monastic manors and religious houses in eight counties, as well as three houses and a manor in London. The nucleus of his estates was in Hampshire: Quarr Abbey on the Isle of Wight (granted in 1537); the eleven manors and 5000 acres of Titchfield Abbey (1537); Beaulieu Abbey (1538); and Micheldever Manor, purchased from the king in 1544. Wriothesley made Titchfield the centre of his domain and transformed the buildings into a residence befitting the rising bureaucrat and courtier. Leland wrote that 'Mr Wriothesley hath buildid a right stately house embatelid, and having a goodely gate, and a conductecastelid in the midle of the court of it' (Itinerary, 1.281). Yet even as he sought wealth and status he was not insensitive to others' needs. When his agent, John Craford, advised him that many local inhabitants were sanctuary men in Beaulieu Abbey he allowed them to remain there for life.

In contrast to the self-assured advancement of his career and fortunes Wriothesley had an ambiguous and potentially dangerous relationship with Stephen Gardiner, bishop of Winchester. On the one hand they had a range of connections which were conducive to a positive, co-operative relationship: their time at university and afterwards his admission to Gardiner's household; his wife's kinship with the Gardiners; the friendship between Wriothesley and the bishop's nephew Germayne, who addressed him as his 'good loving brother' (LP Henry VIII, 12/1, no. 1209); and the two men's common service to the king. The bishop was increasingly alienated, however, by Wriothesley's apparent enthusiasm for reform, especially by his opposition to superstitious practices and their exploitation. This was given practical expression when he destroyed the shrine of St Swithin: 'which done we intend both at Hyde and St Mary's to sweep away all the rotten bones that be called relics' (LP Henry VIII, 13/2, no. 401). He was outspoken in his anticlericalism and particularly critical of bishops' temporal powers. During Gardiner's embassy in France in 1538 Wriothesley provided Cromwell with intimate inside information about the bishop's household in order to discredit him. In July 1538 he came face to face with the returning bishop on the London–Dover road. It was an awkward meeting, during which Gardiner was excessively courteous. With 'no more than a beck and a good morrow with Germain' Wriothesley went on his way as Henry's ambassador to the regent of the Netherlands. His mission was a vain attempt to negotiate marriages between his royal master and the duchess of Milan and between Princess Mary and Don Luis of Portugal. When he returned to England in March 1539, just in time to prevent the regent from forcibly detaining him, he learned of his election to the House of Commons as a knight of the shire for Hampshire, achieved by Cromwell's direct electoral intervention in what Gardiner regarded as his parliamentary domain.

Royal Secretary and Chancellor

On 6 January 1540, a month after Wriothesley had been sent to Hertford to secure the consent of Princess Mary to her prospective marriage with Philip of Bavaria, Henry married Anne of Cleves. His distaste for his new bride was so great that Wriothesley pleaded with Cromwell, 'For Godde's sake, devyse for the relefe of the King; for if he remain in this gref and trouble, we shal al one day smart for it' (Strype, 1/2, appx 462). He was deeply involved in proceedings to that end, giving evidence of the king's distaste and of his consequent non-consummation of the marriage. He was also sent with the duke of Suffolk and the earl of Southampton to advise Anne that the king intended to terminate the marriage and to obtain her consent to this. In April 1540 the insecure Cromwell secured the appointment of Wriothesley and Ralph Sadler as joint principal secretaries to the king. The warrant of appointment dispensed with the statutory requirement of 31 Hen. VIII c. 10, that the principal secretary was to sit in the House of Lords, as both men 'may do the King service in the Nether House “where they now have places”' (LP Henry VIII, 15, no. 437). Wriothesley was also appointed to the privy council (which he regularly attended) and, when Cromwell was created earl of Essex on 18 April that year, the two secretaries were knighted. On 1 August Wriothesley was also appointed commissioner to take and receive recognizances within the verge of the king's household.

The fall of Cromwell in June 1540 resulted in a prolonged period of political instability. The clients and supporters of the dead minister at once came under threat from a conservative resurgence. Although Wriothesley rapidly distanced himself from his former employer he was subjected to examination. He was even accused by Walter Chandler of slander against the king and of unjust retention of some manors near Winchester. However, the charge was judged malicious, and in December 1540 Chandler was compelled to apologize to Wriothesley before the privy council. Nevertheless Wriothesley moved to come to terms with the political changes. Richard Morison later wrote of him that 'he was an earnest follower of whatsoever he took in hand, and very seldom did miss where either wit or travail were able to bring his purpose to pass' (CSP for., 1547–53, no. 491). So the secretary secured his position now by a rapprochement with Gardiner. On 26 July 1540 the revival of his fortunes was marked by the royal grant in fee of the 'great mansion' within the Austin Friars, London. His revived relationship with Gardiner also proved to be lucrative: for example, in October 1542 a grant of the mastership of the game in Fareham Manor and annuities worth £86, because of the bishop's 'great love and singular affection' for Wriothesley (Redworth, 180). This continued generosity, supposedly conditional upon the secretary's willingness to act against heretics, later aroused the jealousy of William Paget.

Political life at Henry's court remained full of rumour, uncertain, and even hazardous. Nevertheless, the later Henrician years were a time of advancement for Wriothesley, who enjoyed growing influence and royal favour. Only when the king met Wriothesley and Norfolk secretly and went with them to an all night privy council meeting at Southwark Palace did he accept the truth about Queen Catherine Howard. Wriothesley and Southampton searched the duchess of Norfolk's Lambeth house for evidence; the secretary examined and extracted confessions from her music teacher Henry Manox and the courtier Francis Dereham; and finally, on 13 November 1541, he went to Queen Catherine at Hampton Court and 'declared certeine offences that she had done in misusing … wherefore he there discharged all her household' (Wriothesley, 1.130–31). In the following weeks he was prominent in examination of the duchess of Norfolk and her household.

During the final years of Henry VIII's reign Wriothesley was active and wide-ranging in his service to the king. On 29 January 1543 he became joint chamberlain of the exchequer. In 1542–4 he worked closely with the imperial ambassador Eustache Chapuys, to revive an Anglo-Habsburg alliance against France; in February 1543 Chapuys, Gardiner, Wriothesley, and Bishop Thomas Thirlby of Westminster concluded such an alliance, and Wriothesley also frequently acted as intermediary, messenger, and informant between king and emperor. In October 1543 Henry commissioned the same three Englishmen to negotiate a league with Charles V, one that resulted in a joint invasion of France a year later. On 26 June 1544 Wriothesley also joined Suffolk and Paget to sign a treaty with the fourth earl of Lennox, in which the latter undertook to work for an English victory in Scotland. On 9 July he was named as one of Queen Katherine Parr's regency council during the king's absence in France, after he had briefly acted as treasurer of the wars (January–April 1544). Before and afterwards he was burdened with a number of fund-raising responsibilities, including administration of a London loan (1542), the 1545 subsidy collection, commissions of array for six southern counties (1545), and the victualling of Calais in July 1546. The strain had become evident by October 1545, when he lamented to Paget that he did not know 'howe we shall possibly shift for thremonethesfolowing' (State Papers Published under … Henry the Eighth, 11 vols., 1830–52, 1.839–40).

"Henry VIII showed his confidence in Wriothesley when the chancellor, Baron Audley, who was seriously ill delivered up the great seal on 21 April 1544. Next day Wriothesley was authorized to exercise the office, and on 3 May, after Audley's death, he became lord chancellor. He continued to be heavily involved in administrative and financial business, however, and so, on 17 October 1544, a commission was granted to Sir Robert Southwell, master of the rolls, and three masters of chancery 'to hear and determine matters in Chancery in place of Lord Chancellor Wriothesley, who is occupied in the King's affairs' (LP Henry VIII, 19/2, no. 527 (24)). He accumulated offices and with them more responsibilities: the constableship of castles at Southampton (from 7 July 1541), Christchurch (20 February 1541), and Portchester (28 October 1542); JP for Hampshire from 1538; the stewardship of Christchurch and Ringwood, Hampshire, from 20 February 1541, and of the forfeited lands of Margaret, countess of Salisbury, from October 1542; and joint clerk of the crown and attorney of king's bench (from 1542, with Thomas White). He also continued to sit in parliament. He was re-elected for Hampshire in 1542, and during the first session Henry VIII required him to report on a Lords' debate on Ireland.

As lord chancellor, Wriothesley summoned parliament in 1545, opened it, and presided over the upper house. He also secured a private act confirming his exchange of lands withthe bishop of Salisbury and the earl of Hertford. In the second session (January 1547) he was one of those authorized to sign acts in the absence of the dying king. The late Henrician years, between 1540 and 1547, marked the peak of Wriothesley's career and reputation. He was praised by the king and also by Chapuys, who in 1542 described him as one of 'the two people who enjoy nowadays most authority and have the most influence and credit with the king', the official 'who enjoys most credit' with Henry, and the man 'who nowadays … almost governs everything here' (CSP Spain, 1538–42, no. 244; 1542–3, nos. 14, 74, 85). He also acted as an intermediary, forwarding ambassadorial requests to the king and delivering royal messages to Chapuys, as they worked to revive the old alliance against France. His wide-ranging services and the consequent respect and favour in which he was held brought their due rewards. These ranged from a £100 annuity in 1544 to thirty-five ex-monastic manors in Hampshire and five other southerncounties, granted in 1544–6. On 1 January 1544 he was elevated to the peerage as Baron Wriothesley of Titchfield; he was elected a knight of the Garter on 23 April 1545; and on the following day his son was baptized Henry with the king standing godfather."

Conservative Champion

Wriothesley's prominence in government meant that he was actively employed in enforcing the conservative religious policy of Henry's final years. Rich, Bonner, Wriothesley, and especially Gardiner were prominent among the royal servants, some of them rigorous Catholic conformists, who sought to expose and punish not only individual evangelicals but also their support networks of friends, followers, patrons, and protectors, especially in the court. Whether or not Henry was actively responsible for the persecution or simply susceptible to Gardiner, who at Windsor in 1543 complained that heresy had crept into every corner of the court and even into Henry's privy chamber, he certainly authorized or allowed a search for reformers. Wriothesley was prominent in the business. In 1543 he examined the musician John Marbeck before the privy council; in 1546 he extracted from Dr Edward Crome the names of confederates at court, in London, and the countryside. In the same year he arrested George Blagge of Henry's privy chamber, tried him at the Guildhall, and sentenced him to death by burning. When the king learned of this he was 'sore offended' and ordered Wriothesley 'to draw out his pardon himself' (Acts and Monuments, 5.564). As lord chancellor he frequently sentenced reformers to the pillory and other penalties in Star Chamber.

Wriothesley did not restrict his activity to protestants. In 1545 he publicly punished a Catholic priest for counterfeiting a miracle; another stood at the Cheapside pillory and was burnt in both cheeks for a false accusation. Nevertheless the most notorious example of Wriothesley's harshness concerned a protestant heretic, Anne Askew. She was summoned by him in May 1546 and examined in order to expose her connections with Queen Katherine Parr, the duchess of Suffolk, and the countess of Hertford. Her stubbornness led to her imprisonment in the Tower, where she was racked. According to Foxe, using what he claimed was Anne's own account, her continued obstinacy prompted Wriothesley and Rich to rack me with their own hands, till I was nigh dead' (Acts and Monuments, 5.547). To have racked a woman who should have been protected by law, both because she was a gentlewoman and because she had already been condemned, 'without some signal from the king' would have been very dangerous, especially as the chance of keeping it secret 'would have been slim', and it has been argued that acting thus would have been 'too great a risk for Wriothesley to take, even for an opportunity to remove potential rivals … such as Hertford' (Redworth, 236, n. 22). Nevertheless the balance of probabilities is that Wriothesley did do as Anne claimed, a sign of his desperation for political advantage which was also potentially disastrous for his future. He was present at Anne Askew's execution on 16 July 1546, having also attended when Crome recanted in a sermon preached on 27 June.

Anne Askew was executed as the decline of Henry VIII's health was causing politicians increasingly to prepare themselves for the next reign. Wriothesley's exact religious position is seldom clear, and may well have been subordinated to his temporal aspirations. Askew herself demanded of him 'how long he would halt on both sides?' (Acts and Monuments, 5.544). An ambitious trimmer, he acted against her in 1546 at a time when the tide was flowing against religious reform, in order to expose her evangelical religious associates among the wives of powerful men and potential rivals at court. These included friends and servants of Queen Katherine, who frequently urged religious reform on Henry. On one occasion in 1546 he lost patience and gave Gardiner and Wriothesley leave to draw up charges against her which he actually signed. According to Foxe, whose account reflects protestant opinions of Wriothesley and his accomplices, this was a plot engineered by Gardiner to remove the reform-minded queen. The attempt to bring down Katherine and her household was also designed to pre-empt the return from France of John Dudley and Edward Seymour. They, too, were inclined to religious reform and they were also Henry's favoured military commanders. Wriothesley was closely involved in the proceedings against the queen and it was he who came with a body of armed men to arrest her and three of her ladies as they walked with the king in the garden. But Katherine had persuaded the king that she was no heretic, and now Henry angrily rebuffed the chancellor, calling him knave, beast, and fool, and drove him away.

When Seymour and Dudley returned the conservative cause was lost, and Wriothesley began to switch sides. He performed his last major service to King Henry in the proceedings against the Howards, who were leading figures among the religious conservatives. He assisted Henry in drawing up the accusations against the earl of Surrey, detained the earl in his house for several days, examined him, and drafted the charges and a list of interrogatories. He was also one of the commissioners at his trial on 13 January 1547. He also witnessed the written confession of Surrey's father, the third duke of Norfolk, and headed the commission which notified parliament of the royal assent to the bills of attainder against the two men. He was naturally active in proceedings against the Howards as Henry's dutiful lord chancellor. It is clear, however, that he was also distancing himself from the other conservatives, led by Gardiner, as they too fell from favour in 1546–7. Gardiner was excluded from the court and the king's will and he was infrequently called to the privy council. The fact that Wriothesley arranged Surrey's humiliating street walk to the Tower is a confirmation of his welltimed political shift. However, it should be said that he was usually willing to act harshly, even brutally, in the king's service. In January 1545, for example, he sentenced Alderman Richard Rede to be sent on military service against the Scots, to punish him for failing to contribute to a benevolence.

Fall From Power

On 31 January 1547 the tearful lord chancellor announced the king's death to parliament. Nevertheless Wriothesley was an immediate beneficiary of his demise. Henry's will named him one of sixteen executors and privy councillors and the recipient of £500. Paget's deposition as to the late king's intentions included an earldom and, on 16 February, he was duly created earl of Southampton with an annual allowance of £20. On 5 February he was appointed chief commissioner of claims for the coronation of Edward VI, at which he bore the sword of state on the 20th. Yet only a fortnight later, on 6 March, the great seal was taken from him, he was confined to his home at Ely Place, and he had to give a recognizance of £4000. Although he remained a privy councillor he was excluded from the council board. His ostensible offence was abuse of authority. Presumably because he expected to be preoccupied with government business, on 18 February he had sealed and issued a commission to four civilians to hear and determine all causes entered into chancery. This relieved him of many legal duties. '[D]ivers studentes of the Commen Lawes' petitioned the government that this had diverted business from the common law courts to chancery insomuch 'as very fewe matters be now depending at the Comen Lawes' and that, in other ways too, the chancellor was prejudicing the common law (APC, 1547–50, 48–50). Southampton's commission was referred to the judges and the king's law officers. They found him guilty of issuing a commission without a warrant or consultation with the other executors. Furthermore he had 'menassed divers of the said lerned men and others' (ibid., 56). Abuse of his authority, however, was only the pretext for his fall. His commission of 1547 was no different from that of 1544; he had the authority, like his predecessor, to issue such commissions; and there exist copies of Edward VI's authorization of the lord chancellor's warrant to make such commissions. The chief cause of Southampton's fall was his animosity to Edward Seymour, formerly earl of Hertford, and now duke of Somerset, and his opposition to the office of protector. As he later told Charles V's ambassador, François van der Delft, his troubles were the result of Somerset's long-time enmity towards him and of his own refusal to 'consent to any innovations in the matter of government beyond the provisions of the will' (CSP Spain, 1547–9, 91–2, 100–01, 106). On 31 January 1547, three days after Henry VIII's death, the late king's executors made Somerset lord protector, in accordance with the authority bestowed on them by his will. He was, however, required to abide by majority decisions, which strictly limited his power. Southampton opposed any change which would reinforce Somerset's authority or freedom of action and, so long as he held the great seal, no further change was possible. It was a group of senior government lawyers who solved Somerset's problems. Led by Baron Rich and Sir John Baker they brought to light what was merely a technical error in the commission to the civilians issued by Southampton, and exploited it to secure his dismissal as chancellor. When he surrendered the great seal it was promptly used to give legal authority to a patent issued by the young King Edward VI, which not only made Somerset protector of the realm and governor of the royal person, but also invested him with the power to choose the privy council and to control its business.

Southampton's fall neutralized a possible political rival to Somerset, who was also his personal enemy. Southampton's bold, sometimes harsh actions, and his outspoken manner (which included past criticisms of Somerset) were arguably also the responses of a loyal, dedicated royal servant. But he was also undeniably ambitious, and fully capable of alienating others, for instance by his conduct in religious affairs. He also resisted proposed reforms which would have expanded the court of augmentations' jurisdiction and so harm the interests of chancery, especially the fees received by its officials. In 1547 a bill to create a new court of augmentations was placed in his charge, but it did not proceed, thereby thwarting its promoters. When Henry died Wriothesley was isolated. He was also vulnerable because, according to Paget, he was arrogant and, in Richard Grafton's words, he was guilty of 'overmuch repugnyng to the rest in matters of Counsaile' (Grafton, 2.499–500). When Southampton fell, however, he submitted to his sentence, publicly acknowledging it to be a just one. He was released on 29 June 1547, his fine was remitted, and by 17 January 1549 he had resumed his place at the council board. He regularly attended parliament in 1547 (thirty-three of thirty-five sittings) and 1548–9 (sixty-one of seventy-three), and he was active in both sessions. In particular he resisted protestant religious innovation, though not, perhaps, as energetically as he might have done, for on 20 February 1549 the imperial ambassador reported that 'the ex-Chancellor lost his constancy in the end and agreed to everything' (CSP Spain, 1547–9, 345).

Defeat and Death

Although Southampton's political fortunes revived he bore a continuing grudge against the protector as the man responsible for his fall. However, when Thomas, Baron Seymour of Sudeley, conspired to overthrow his brother Somerset and assumed that Southampton would assist him, the earl advised him not to intrigue and raise faction. '[F]or my parte thank God of yt, when I was at the worst rather than I wolde have consented in my harte to any faction or partie tumult. If I had had a thousande lives I woulde have lost them all … than attempt yt' (TNA: PRO, SP 10/6, no. 15). Southampton was sufficiently astute to realize that to ally himself with the protector's brother would be disastrous. When the doomed Thomas Seymour was imprisoned Southampton was a member of the joint parliamentary committee which interrogated him in February 1549.

Nevertheless Southampton was active in conciliar moves against the protector in October 1549. By then he had moved back to the leadership of a group of religious conservatives, including the twelfth earl of Arundel. Although Warwick and the evangelicals shared with the conservatives an immediate common objective, to topple the protector, the alliance was an unnatural one. It was, however, in the short term a successful one, and once the protector had been removed Southampton enjoyed a brief period of prominence, during which he was appointed to attend upon Edward VI. 'Wriothesley … is lodged … next to the king. Every man repaireth to Wriothesley honoureth Wriothesley, sueth unto Wriothesley … and all thinges be done by his advise' (Ponet, sig. Iiii–iiiv). Warwick, however, feared a Catholic coup, intended to make Mary regent, and with good reason, because by December 1549 Southampton and Arundel sought not only Somerset's destruction but his own too. Warwick knew it, and said as much. At a council meeting in January 1550 he put his hand on his sword and told Southampton: 'my lord you seeke his bloude and he that seeketh his bloude would have myne also' (Hoak, 256). By 14 January 1550 Southampton and the earl of Arundel had been expelled from the court and placed under house arrest, while their associates, such as the fifth earl of Shrewsbury and Sir Richard Southwell, were removed from the centre of government.

Southampton now ceased to attend council meetings and in February he was removed from the council list. He was also seriously ill. Although his condition improved in March he was reported to be 'desiring to … be under the earth rather than upon it' (CSP Spain, 1550–52, 47), and on 28 June he was allowed for reasons of health to retire to Titchfield. He was too ill to travel, however, and on 30 July 1550 he died at his London home, Lincoln House in Holborn, which he had obtained by exchange with Warwick. According to Ponet, 'fearing least he should come to some open shamfullende, he either poisoned himself, or pyned awaye for thought' (Ponet, sig. Iiiiv). The fact that he was repeatedly ill of a quartan fever suggests that he may have been a consumptive, possibly the cause of death. He was buried in St Andrew's Church, Holborn, on 3 August, but his body was later removed to Titchfield. His will, dated 21 July 1550, was proved on 14 May 1551. Apart from the usual bequests to family, servants, and friends he gave gilt cups to 'my verie goodLordes therles of Warwick and Arrundell'. And 'for a remembrance of my duetie toward my sovereigne Lorde, and for the great benefites that I have receaved of his most noble father of famousememorie', he granted Edward VI the income from fourteen manors and other lands in five counties during his son's minority (TNA: PRO, PROB 11/34, fols. 97v–98).

Assessment

In 1551 Sir Richard Morison wrote that 'I was afraid of a tempest all the while Wriothesley was able to raise any … I never was able to persuade myself that Wriothesley could be great, but the King's Majesty must be in greatest danger' (CSP for., 1547–53, no. 491). Some had a very different opinion. Leland praised his intellect, character, and probity. He certainly had high ambitions, and as he realized them so he assumed the airs and graces of a new member of the élite. By 1545 he was licensed to retain 140 men in his livery, and whenever he appeared in public he was preceded by his gentlemen and followed by his yeomen clad in velvet and gold chains. He rebuilt Titchfield as a residence fit for a king to visit, which Henry VIII did on 31 July 1545. According to Foxe, whose portrayal was later accepted by Burnet, Lodge, Strype, and others, Wriothesley was a careerist who was also variously a zealous papist, a Romanist, even leader of a popish party, and certainly a Catholic. His acceptance of the royal supremacy and his enthusiastic destruction of shrines, tombs, and relics make it impossible to be so certain. Indeed his sharp criticisms of bishops, the religious formula adopted in his will, his patronage of reformers such as Richard Taverner and Robert Talbot, the choice of John Hooper to preach at his funeral, and the fact that his children's teacher landed in trouble for heresy, all suggest that Wriothesley had some protestant sympathies. His true religious convictions were masked, however, by his social and political conservatism, the precariousness of court politics, and especially by the devoted loyal service of an obedient royal servant.

Wriothesley helped to implement royal religious policies, whether they were in a Catholic or a protestant direction. He profited from the dissolution of the monasteries, but he also drafted a paper on ways in which monastic wealth could be used to establish new hospitals, build highways, and maintain the army. He was respected as a lord chancellor who protected royal interests and rule of law. His dicta were repeated: that while force awed, justice governed the world; and that every man who sold justice sold the king's majesty. He was respected for other qualities too. Roger Ascham addressed him as a great patron of both literature and the University of Cambridge, while Leland referred to him as a friend to the muses, and in 1537 his servant John Huttoft gave 'immortal thanks for your goodness' (LP Henry VIII, 12/2, no. 546). Yet he was at the same time unbending and even cruel to those who opposed or offended royal wishes. He could also be without scruple—in 1547, immediately after Henry VIII's death, he, Warwick, Arundel, and Baron Russell all reduced their tax assessments.

-

- LP Henry VIII, vols. 4–21

-

- CSP Spain, 1538–52

-

- CSP for., 1547–53

-

- A. J. Slavin, ‘The fall of Lord Chancellor Wriothesley: a study in the politics of stability’, Albion, 7/3

-

- (1975), 265–86

-

- will, TNA: PRO, PROB 11/34, sig. 13, fols. 96v–98v

-

- J. Strype, Ecclesiastical memorials, 3 vols. (1822)

-

- A. J. Slavin, ‘Lord Chancellor Wriothesley and reform of augmentations: new light on an old court’,

-

- Tudor men and institutions, ed. A. J. Slavin (1972)

-

- J. Ponet, A short treatise of politike power (1556) [in Theatrum orbisterrarum (1972)]

-

- GEC, Peerage, new edn

-

- VCH Hampshire and the Isle of Wight, vols. 2–5

-

- Calendar of the manuscripts of the most hon. the marquis of Salisbury, 1, HMC, 9 (1883)

-

- APC, 1542–54

-

- Select works of John Bale, ed. H. Christmas, Parker Society, 37 (1849)

-

- G. Redworth, In defence of the church catholic: the life of Stephen Gardiner (1990)

-

- BL, Add., Harley and Stowe MSS

-

- A. L. Rowse, ‘Thomas Wriothesley, first earl of Southampton’, Huntington Library Quarterly, 28

-

- (1964–5), 105–29

-

- HoP, Commons, 1509–58, 3.663–6

-

- C. Wriothesley, A chronicle of England during the reigns of the Tudors from ad 1485 to 1559, ed. W. D.

-

- Hamilton, 2 vols., CS, new ser., 11, 20 (1875–7)

-

- The itinerary of John Leland in or about the years 1535–1543, ed. L. Toulmin Smith, 5 vols. (1906–10);

-

- repr. with introduction by T. Kendrick(1964), vol. 1

-

- Literary remains of King Edward the Sixth, ed. J. G. Nichols, 2 vols., Roxburghe Club, 75 (1857)

-

- CSP dom., 1547–80

-

- M. A. R. Graves, ‘The Tudor House of Lords in the reigns of Edward VI and Mary I’, PhD diss., Otago

-

- University, 1974

-

- J. J. Scarisbrick, Henry VIII (1970)

-

- G. R. Elton, Tudor revolution in government (1953)

-

- H. Ellis, ed., Original letters illustrative of English history, 1st ser., 2 (1824); 2nd ser., 2 (1827)

-

- The acts and monuments of John Foxe, ed. J. Pratt [new edn], 8 vols. in 16 (1853–70)

-

- S. Brigden, New worlds, lost worlds: the rule of the Tudors, 1485–1603 (2001)

-

- R. Grafton, Chronicle or history of England, 1189–1558, 2 vols. (1809)

-

- D. E. Hoak, The king's council in the reign of Edward VI (1976)

-

- E. W. Ives, ‘Henry VIII's will—a forensic conundrum’, HJ, 35 (1992), 779–804

-

- E. W. Ives, ‘Henry VIII's will: the protectorate provisions of 1546–7’, HJ, 37 (1994), 901–14

-

- state papers domestic, Edward VI, TNA: PRO, SP 10/6

-

- R. W. Goulding, ‘Wriothesley portraits’, Walpole Society, 8 (1920), 17–94

-

- BL, political corresp., Add. MSS 32647–32652, passim

-

- Hants. RO, personal, official, and estate papers

-

- TNA: PRO, Wriothesley papers, SP 7

-

- BL, Harley MSS, corresp.

-

- TNA: PRO, SP 1

-

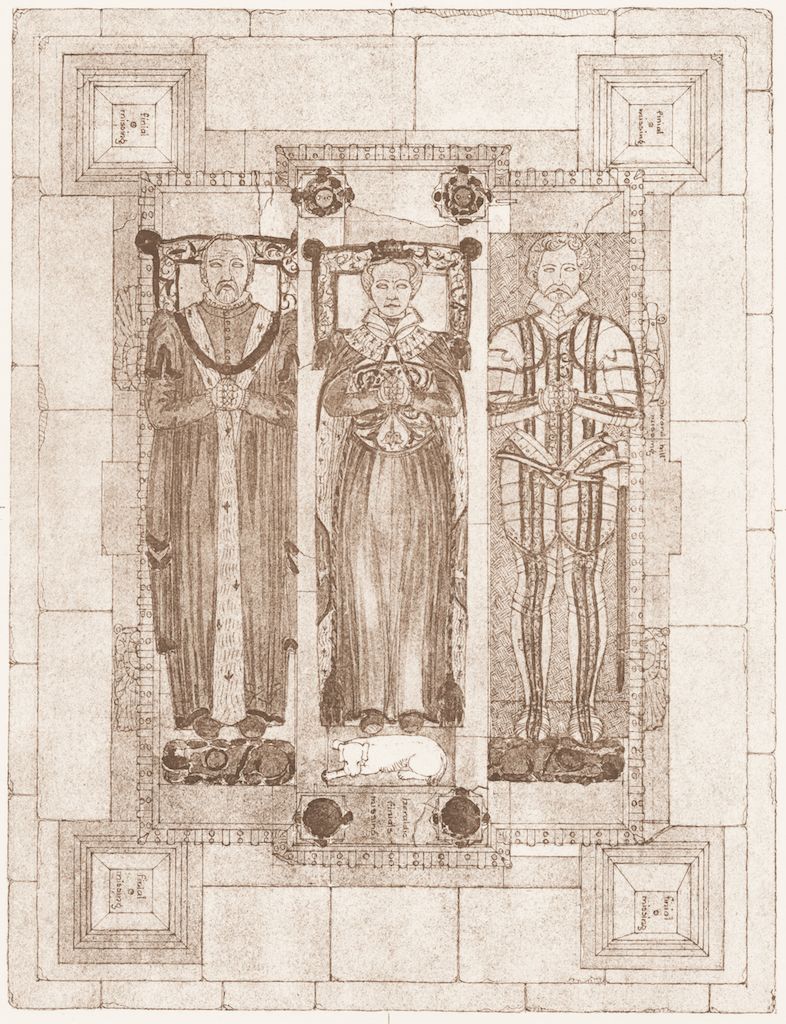

- Southampton Monument, Parish Church of St. Peter, Titchfield, Hampshire, UK

-

- H. Holbein, miniature, 1538, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

-

- H. Holbein the younger, chalk drawing, 1538?, Louvre, Paris

-

- Group portrait, oil on panel, c.1570 (Edward VI and the pope), NPG

-

- Oils (after type by H. Holbein the younger, 1538), Woburn Abbey, Bedfordshire

-

- Portrait, Beaulieu

-

- Thomas Wriothesley, 1st Earl of Southampton, ©National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG D2577by Edward Harding, published by E. & S. Harding, after Silvester (Sylvester) Hardingstipple engraving, published 1 November 1794

- NPG D24827

-

- Considerable: TNA: PRO, PROB 11/34, sig. 13, fols. 96v–98v

View the article for this person in the Dictionary of National Biography archive edition.

See also

-

- Writhe, John (d. 1504), herald

-

- Wriothesley [formerly Writhe], Sir Thomas (d. 1534), herald

-

- Wriothesley, Charles (1508–1562), herald and chronicler

-

- Wriothesley, Henry, second earl of Southampton (bap. 1545, d. 1581), magnate

External resources

Bibliography of British and Irish history

National Archives

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Wriothesley, Thomas, first earl of Southampton (1505–1550)

Entry by Michael A.R. Graves , Copyright © Oxford University Press 2019

Reproduced with permission of the Licensor through PLSclear.

Published in print: 23 September 2004

This version: 03 January 2008

Visitors may consult content provided by Oxford Publishing Limited for research and study purposes only. Any further use, including, but not limited to, unauthorized downloading or distribution of images or editorial content is strictly prohibited. Visitors must contact the Oxford Publishing Limited (facilitated by PLSclear) at plsclear@pls.org.uk.

Last will and testament dated 21 July 1550

TNA: PRO, PROB 11/34, sig.13, fols. 96v–98v

Modern spelling transcript copyright ©2016 Nina Green All Rights Reserved

WRIOTHESLEY, Thomas (1505-50), of Micheldever and Titchfield, Hants and Lincoln Place, London.

Published in The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1509-1558, ed. S.T. Bindoff, 1982. Available from Boydell and Brewer. Visitors/readers may consult content provided by the History of Parliament Trust for research and study purposes only. Any further use, including but not limited to unauthorized downloading or distribution of images or editorial content is strictly prohibited. Visitors must contact the History of Parliament Trust directly.